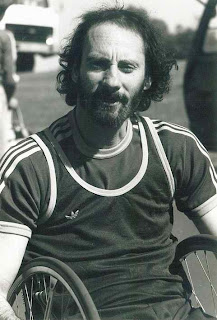

Peter Marsh was born in 1948 in Brisbane and grew up in Brisbane. In 1970 he severely injured his spinal cord in a football accident. He went on to compete in the Paralympics in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This is his story:

On Queen’s Birthday weekend in 1970 Peter had his accident. “It was a typical morning of a game, nothing outstanding, nothing different, just got up and had some breakfast and got ready to go to the game, just the ordinary preparation that I normally do. I probably got there at 11 o’clock because we play at 12.00.

“We played at Lang Park and against the team called Valleys who were playing fairly well that year. We weren’t playing well at all. We were about second last or last in the competition and it was my first year in what you call “senior football” in the C grade. So it was just a normal game. I don’t know what the score was, but we were probably getting beaten at the time. We’d been playing 20 to 25 minutes. I remember looking up at the clock at one stage and thinking – how long is this going to be going for. And we had a scrum 20 metres out from our line, the ball come out behind the scrum and the halfback gave the ball to me and I ran across field a bit and this, it’s a little bit of a blur, except I remember screaming and, obviously everything stopped and I was having trouble getting my breath. I said to one of the guys – can you straighten my legs out. He said – mate, they’re already straight and I thought – ah, I’m in a spot of bother here. An ambulance came and put me on a stretcher. Went to the sideline and one guy told me later on that they were squeezing, pinching my skin to see if I could feel anything and obviously I couldn’t. So it was then in to the ambulance off to Royal Brisbane Hospital where they eventually did an operation on my neck, which was unusual in those days. They did a bone graft for all of my vertebrae from C1 to C7 and even wired it. I injured my neck quite a few years after that and I asked the radiologist – is my neck all right. The radiologist said – mate, that’s probably one of the strongest parts of your body. They strengthened it by doing all that. So that was a bit of a crazy day, that one.

“I had no idea what a spinal injury was. There were very few that we knew about in those days. There may have been plenty more, but they didn’t really hit the headlines or anything. It wasn’t long after me that a footballer died of a spear tackle and there was a photograph of it in the paper. He was turned right upside down and speared into the ground and broke his neck and that’s when there’s more interest taken. So they became more well known then and people obviously knew then if you had a spinal injury then in all probability you wouldn’t walk.

“It was Brisbane Cup day and I had been a racing enthusiast as long as I can remember. The night before we were at a friends for a barbecue for my girlfriend, her boss had a horse running in the Brisbane Cup so we were out there and everyone was hopeful about the horse’s chances etc. and so, if I had’ve had a choice I probably would have gone to the Brisbane Cup that day instead of having to play football, but so when I got to the hospital, was probably around 3 o’clock, I just wanted to know who won the Cup – and he ended up coming third.

“I didn’t really realise the extent for some time and maybe that was denial. I would think it was just ignorance. I had no idea really. I know it was pretty uncomfortable, not very enjoyable to lay on a rotor bed, what they called it and we’d lay there for four hours and they’d come and put, basically a mattress on top of you and then turn you right over so you’re on your belly for five or four hours, and looking at the ceiling for four hours. I didn’t know the implications of bladder/bowels, all those sort of things until obviously you’re going on and you’re thinking – what’s going on here. How do I do this and how do I do that? It’s a learning experience and you had to learn the hard way, there was no easy way. People could tell you but you’d think, you know.

“I had about a month in the Royal Brisbane and went over to the Spinal Injuries Unit at the Princess Alexandra Hospital, which is still there of course. But it was such a lot of difference between now and what it was then. It was a dinghy old hole and I thought by about that time that well, this is it, the beginning of the end probably. You had cockroaches up the wall, paint off the walls, not a very pleasant place, run by a Professor who was about 86 years old. I can still remember everyone telling you to drink, you must drink water, drink water, drink water, drink water. That’s obviously to keep your kidneys flushed, but there was only so much water you could drink. It was difficult. My girlfriend came and saw me every night. My best mate came up every night and saw me and that sort of thing. Mum and Dad of course and all that, so I had a lot of family support. Reminded me that when I was up and about there was a 16 year old girl from Mount Isa who actually didn’t have any parents, no one to support her, no one to help her and I thought, boy, how tough was that. There were maybe 20 people there, cause you stayed in a lot longer in those days than you would now. I had nine months at the Spinal Injuries Unit, whereas now you’d probably have three or four.

“Through the sport I got to know people who’d been to wheelchair games and things around the country and a couple of guys mentioned the spinal unit in Perth was the leader in Australia by a country mile and my bladder wasn’t too bad and by that I mean, back in those days you put a, virtually a condom type of thing on your penis with a hole in the bottom of it which had a tube that led into a bag that you attached to your leg. The old professor thought if you could pee, that was about a good enough – okay you can go home now you can pee. So I had a residual of something like 200 ml or something that would be left in your kidneys and bladder after you’ve had a pee so, it was obvious that people got infections and stuff like that from that. So I went to Perth with assistance from the football club. They paid for the trip and stuff. Before I left, I wrote to them of course and asked if they could help me and basically they said – sure come on over, if you can get here, we’ll help you. So I got that residual down to about to about 5 mls after a minor operation and it was marvellous and that meant, by doing that if I can empty my bladder properly, I didn’t need to use any aid or anything because if you know your bladder’s empty, it’ll take at least two hours to fill up, so you only used a urine bottle. You could pee any time you needed to basically and that was a revelation for me, came back and I was very pleased. It was very helpful, they were terrific.

“I went over to Perth for probably a month or two and got on well with a lot of people there who said why don’t you stay for a while and I thought okay, sounds good. So I encouraged the girlfriend to come over and I was there from September to March the next year, so that would have been September ’71 till March ’72. That was good. I met my first wheelchair coach, sports coach, yeh he died only a couple of years ago, lovely fellow, Frank Ponter, marvellous athlete himself back in the old days of course, not any more. He did everything, his first Games were in 1960 in Rome when the first Paralympics were on.

“Under Frank I trained pretty hard before I left Perth and I wrote to the Queensland organisation to tell them, I’m on my way home and could I represent Queensland in the Nationals in March 1972, after I told them what I’d been doing. I could represent Queensland there in Sydney on the way back’d be great and the Queenslanders all went down in a convoy of cars to Sydney and I flew over from Perth to Sydney and stayed at my sister’s place and bought a car there and so I was able to drive home with them basically. So I competed in my first games there and it was an interesting experience. Everything was different then, I mean, I pushed over 60 metres, I think it was in those days. You know in just the basic ordinary chair that everyone else was using. I used the wheelchair for track and it was not very fast. But I think I did shot putt and discus and played table tennis as well, yeh.

“I thought – this is all right, this is good and I was reasonably successful, against very moderate opposition. I don’t mean that in a bad way, I mean, there weren’t the numbers. There was only a couple of us that would compete probably in some events so you could pick up a bronze medal by doing not much. The sport was like that for a little while. So I still won plenty of medals, some of them weren’t perhaps as dignified as they could have been. It set me up, realising what goes on in the games and went on to master it.

“Paralympics is often confused with paraplegia, but it means a parallel Olympics and so they want to be parallel to the Olympic Games and that’s basically what it is. So every time there’s an Olympic Games, they have Paralympics, if not in the same city then, in the same country. That’s how it got its name.

“My first Paralympics was in 1976 in Canada, in Toronto. The able-bodied Olympics were in Montreal and ours were in Toronto about two weeks later. It was a great experience. Canada was a lovely place, wonderful people. I only realised when I did a little work on my own background that, I got two bronze in Canada. One was a very ordinary event, not necessarily a blue ribbon event. They put a target on the ground and you’d throw a club at it. They called it a club and it was in the shape of a bowling pin, ten-pin bowls. They had this event and you’d throw the club at a target, similar to javelin where they had precision javelin, where they had a target on the ground and you’d throw the javelins, but you know, in the middle, you got 10 points or whatever it was. I actually was first twice at the Olympics but never got a gold medal and that was one of the events. Three of us had the same score, and one guy was awarded the gold from the count-back and the other two, myself and the other guy were similar or something so we had a throw off and he beat me in the throw off. So that was one bronze. The other was in the 60 metres. Again they only had 60 metres. We were still considered “patients” in those days rather than athletes and they thought that 60 metres was as far as we could go. So I got a third in that.

“It was the first time I’d flown internationally, meeting other people, and sharing stories, what some guys would do, to do this or that or the other thing, picked up a lot of tips on things that you would do and stuff. So it was good from that point of view, such as managing bladder or bowels or anything like that, driving a car or eating, you’ll see someone pick up something, or something or other and think – that’s all right that, and so you’d learn a lot of stuff from it.”

In 1980 the Olympics were held in Moscow, however the Paralympics were held in Arnhem, Holland. Peter explains:

“The Russians publically stated they had no disabled people and as such wouldn’t have Paralympics, which is, a bit strange, so they had to find somewhere else to have them and Arnhem put up their hand. It was a tough games. We had two days when it didn’t rain. Every other day it rained. It was cold. I performed miserably. I can’t remember much about them either. One guy got there. He was one of our best basketballers and didn’t realise that he’d been sitting on the seatbelt on the plane over so he got a very bad pressure area on his bottom, so that meant he had to have a lot of medical assistance. We had coughs, colds, flus and everything. It was just an awful games – for some people, others it was brilliant. My mentor from Brisbane, Mike Nugent, who makes wheelchairs and stuff. Mike put up a fantastic performance to win a 200 metres, world record, gold medal, fantastic. He really deserved it. He’d been round the sport for a long time. So it was only me that was miserable, not everyone.

“The Paralympics gradually grew. Rome would have only had 100 or 200, something like that. By my time they would have had a couple of thousand, probably or a few thousand. Now of course they have tens of thousands. But remember back in those days they only had wheelchair sports. They didn’t have amputees or the blind or anything else, so spinal injuries basically only. We had some polios, but mostly only spinal injured. There’s probably a lot of spinal injured people who wouldn’t compete now. It’s difficult to compete against someone whose got a leg amputated because they have full use of their trunk, back and core muscles etc. Balance is always a problem for us. So that’s the reason why we’ve got so many competitors now because we’ve go so many more disabilities involved. It’s not a good thing, it’s not a bad thing, it’s just a thing.

“1983 was a good year, after 1980 Paralympics, where I performed poorly. One reason was a lack of international competition, so I talked to my coach and we decided if we’re going on to 1984, we would go to what was in those days the world championships in Stoke Mandeville in England in ’81, ’82, ’83, so that we’d be well prepared for ’84. So part of that preparation was we went over and did better every year basically and ’83 I won Gold and world records I think for the 100, 200, 400 and 800. We just had a good year.

“I played a little table tennis as well, but the track was always what it was about. And again in those days then went up to 800 on the track. That’s as far as we were allowed to go. Now, of course quadriplegics do the marathon and have done for quite some time. I was rewarded with some awards and stuff. “We were no longer treated as “patients”. They realised that we had potential to do some good stuff. We did with some modification of wheelchairs, as well. Chairs went a lot faster then than they were originally and go a lot faster now than they did then. But, yeh, it was good. I’d like to think that if I had one contribution to make to the sport, then with a lot of other people we took the whole scope of sport from being outpatients, or patients if you like to athletes over that time. It was good.

“Anne (my wife) was there in ’81 and I saw her and sort of chatted to her. I was always friendly with the Irish team. I suppose just because they’re Irish. And she was part of the staff. She was a helper coach. So when I went back in ’82, I went over to Ireland after the Games with her. My Dad came with me then. ’83, might have been when Dad went, I can’t recall. I went over with her again and she came back with me then. So, yeh, so it was ’81, ’82,’83 that she came back and we got married in ’84.

“The government of those days and the whole sports movement were recognising the efforts of wheelchair sports people. I was nominated obviously through Sporting Wheelies. The year before, a girl from Queensland, Kerri Ann Connor, was named Junior Sportsperson of the Year – full stop, and she was in a wheelchair. So that year I was a finalist in the Performance of the Year and the Male Athlete of the Year. So they were sponsored by the Australian Sports Commission and they were televised live throughout Australia and, I didn’t win. But that didn’t matter. They interviewed me before I went down there and I said, really, I’m a winner already. Just the fact that you go down there and you’re mixing with all of these people.

“I was Sporting Wheelie of the Year. They have one every year, an annual award thing for a long time and I was pleased to win it. I believe it was in ’83. And now I select the Sporting Wheelie of the Year because I’m on the selection committee for awards. You must do your best, basically. But you’ve got to put a bit in to it as well, you know off the training field, I mean and put something back into the organisation as well. “In ’84 the Olympics were in Los Angeles where the Paralympics were going to be and we only found out in January that the organiser of our Games took the money and ran. It was very disappointing so we had to come up with an alternative in a short space of time and because they went to England every year they asked England to do it again and they agreed to do it. So it was thrown together very quickly in England. I think it had a lot to do with my performances over there ’cause I think for me it was just like going back to England again, rather than going to Paralympics again and I struggled psychologically, I struggled big time. I couldn’t push my way out of a paper bag over there. It was terrible. However, I did get a silver and bronze in the relays. That’s another one where we finished first and there was a protest, third against second, so we had to re-run it. We ended up second.

“For our wedding, Anne’s Dad came out. It was good seeing him come out and have a look at Australia. It seemed to be all right except that I picked a bad day to have the wedding day because a lot of my friends in the government were racing enthusiasts, as I was and I picked a day when one of the, probably the second biggest day in racing for my wedding – Cox Plate Day It’s a big day in racing and a number of them said – you’re kidding aren’t you, you’re not having it on Cox Plate Day. But there was a reason for that because we went to Sydney and then to Melbourne for the Melbourne Cup. It was a great day. Everything went well. One of those days that everything’s good. We had a great time.

“My Dad, Col, was great. I had a weightlifting bench over at his place for a long time so I used to come over and do some weights over there. And he’d always help of course. When Mum died, Dad had already been involved to a certain degree with my sport and decided that he’d get more involved. Not only with me but with all the other track athletes that used to go to QE2. He got really involved, loved it all and they had a container over there and he painted the container and they all thought it was wonderful that he did all that. He was one of the first Life Members of the Sporting Wheelies and he was just a great volunteer. Everyone loved him and he was a great help. They began the Col Marsh Volunteer of the Year Award. After he died we went to the organisation and we bought the trophy back then and had a couple of rules that we thought were appropriate for those days to have an award as such and yes, still going and I present it nearly every year. He would have been thrilled to bits with that.

“At my last national games, in Adelaide I was defeated for the first time in track events by my mate at that time Richard from Sydney. He’d got himself into a three-wheeler track chair and I was still in a four-wheeler. He really was out to get me, which good on him, he did and he didn’t compete in every event then but if he had’ve he would have beaten me in every one of them, but Richard was a good friend over a long period of time. Yeh he beat me fair and square so I knew by then it was time to get out.”

Peter was involved with the Sporting Wheelies and Disabled Association for many years.

“Firstly always been a member but not always up until ’89 I was an athlete. I’ve been a team manager on a few occasions, an organiser as in those games, I was on the sports committee for a long time, probably 10 years or so. I’m a volunteer now. Did a lot of other volunteering, coached juniors in particular, selector. I was, along with my coach, delegate to the national body for a number of years.

“We had about three or four meetings a year and we’d go to Sydney or Melbourne, and sit around the table and argue different things and you’d have to be prepared to go down there. You had to report when you came back, that sort of thing. That was difficult to start with cause wheelchair sports is basically run by NSW, Victoria and Western Australia, so Queensland just didn’t get much, but my former coach, she made herself fairly recognised in the sport once she started to talk sense and they started to listen. Before her was Eric Russell who, you could almost say was the Sporting Wheelies in a lot of ways, did a lot to set the organisation up and as a separate identity from the Spinal Injuries Association, as they’re called now.

“Anne was very involved in most junior games that we had. When she came out here she got involved in what they called “come try it days” so junior athletes, kids, young kids would come and try swimming or try track or try field events or try something and see if they liked it, and she told stories a lot. So that was Anne’s main thing, she was as I said involved in some organisational things but juniors were her go. She went on a number of trips within Australia and overseas as an assistant in the sport. They had, over that period of say ’83 to ’92 or something they had a fantastic bunch of committee people for junior sport. They all worked so well together, it was just a marvellous group of people that all wanted the betterment of the kids in their sport so it was just a wonderful group, so Anne was part of that.

“Back in the days when I became involved with the Spinal Injuries Association, it was called the Paraplegic Association. I was on the committee of the Para. Association for a little while and it was obvious that the sport and the organisation needed to go their separate ways and so I was on both at one stage so I did a bit of fundraising and chook raffle stuff and all that for the Paraplegic Association.

“After I’d been to Perth in 1972 I came back and thought, I think I’ve got something to offer people so I did a Social Welfare course at what we call TAFE now and said I want to be a Welfare Officer for the organisation who, at that stage only employed an able-bodied person and it would have been an ordinary wage, cause that was fundraiser, organiser, so the organising committee sort of said okay. I only worked initially for twenty bucks a week which’d cover cost of fuel etc. so you could stay on a pension which I was on back in those days and I remember, it was in ’76. I was at some Paralympic games, and we’d just got a grant, from the government to employ me. We had offices at Spring Hill and to get to there you had to park on the opposite side of the road and we were always getting parking tickets, I remember and ignoring them. Another fellow and myself had to go to court with these parking tickets and we had to pay them because they said, you have to pay them because you parked too long. That was the start of getting out in front and getting in the papers and that went through and that’s when 1981 was The Year of the Disabled, of course and that really kicked things off. We got a lot of benefits out of that year such as a building code and all sorts.

“As a Welfare Officer it was difficult. I used to go up and visit the Spinal Unit every Friday afternoon, introduce myself as a Welfare Officer, and the organisation to them and give them any little leaflets and, next week when I go up maybe they’d say gidday and maybe they’d have a chat or something like that. So it was basically getting out and finding out what they wanted and knowing there was a contact there that they could talk to, especially being in a wheelchair. So they were good days. I think that went till ’83, yes, ’83. I went over to England for the Games in ’83.

“Later I applied to university for entry as a mature age student, Arts I think it was, and got accepted and that’s all I needed, because I didn’t have senior education. That was the comparison to a senior education so that’s how I got in the government in 1983.

“I always said one of the best things I did was build my house. The only thing I did better than that was to live in it by myself. So I was at the time competing at the highest level of sport, living by myself, training and working full time and I thought that was probably when I was at my best. However, in saying that, getting married and having a child was pretty big as well. I thought, before I met Anne, by gees the years are getting away and, you know, I haven’t had a kid and I always wanted to be a Dad. So the wheelchair really for me didn’t come into it because I was living a life the same as anyone else really. The fact that I was in a wheelchair was incidental.

“Best improvements would have to be access. If I had to put it down to one word, it would be “access”. And not just access to buildings, but access to a whole range of things through the government, and that sort of thing. Access to information, and the internet etc. helping set up again wider than I ever expected to. Design of wheelchairs, cars, all those things. I catch a bus every Saturday morning to go down to the club. I wouldn’t have thought catching a bus, I’d ever do that. And it’s simple, it’s easy. Train travel’s better, even better. Trains don’t go round so many corners, and they’re really quiet. Train travel’s terrific, been down the Coast on the train a couple of times. Great way to get down there.”

Peter’s advice to those who have recently experienced a spinal cord injury:

“I used to do that (give advice) a long time ago. If I did have one piece of advice I would suggest to them that the injury you have is not just affecting you. It affects those who love you, the people closest to you are affected in a different way but not in a lesser way. And we tend to get frustrated and angry and all that and take it out on those closest to us and to be wary of that and try not to do it, if you can because that hurts them more than you’ll ever know.”

The future for those with spinal cord injuries:

“I think we pamper them too much. Bit strange, I suppose, but, and it’s the old man syndrome and I hate it, you know, “back in my day, we had to”, but we had to work hard for everything that we could achieve in those days and I fear that a lot of people might start having an attitude, I need this, I should have this and all that. I’m concerned I suppose if they could only think of people in Africa or somewhere like that, if they break their back, what would happen to them. So whilst it’s not ideal and it’s a horrible thing to have to happen, you’ve got to be able to work through it a lot yourself. Take a lot of responsibility yourself for what you’re going to do and where you’re going and that. Try not to let other people do it for you, do it yourself, if you can,. They may be pampered a little bit too much I think, maybe not.

“It’s just not the worst thing that can happen to you. It’s horrible, but, I think, if you had the choice of a spinal injury or losing a loved one, which one would you take. It’s a pretty easy decision to make. I think the death of a loved one is the hardest thing you have to endure.

“I believe the Sporting Wheelies nominated me to carry the Olympic Torch for the 2000 Olympics. You had to have a nomination obviously and that would have been screened somewhere. I was just notified one day in March or April 2000 that I’d been chosen to carry the Olympic torch. I was a little shocked. Didn’t expect it and then of course the anticipation of wondering what the hell, what do I do? So it was interesting. “I was sent the uniform. Everyone wore the same uniform and they told me that they had an implement, or a bracket or something that slid underneath the seat on your wheelchair and the flame or the torch would slip in to that bracket. There turned out to be many many people in wheelchairs and people with disabilities other than that who carried the torch.

“On the day, we went to St Peter’s College at Indooroopilly, and not knowing what was ahead of us from there, so we just went there. On the way I recall having a look side to side on the road and thought – what’s going on? People had got their folding chairs that they’re getting out and having a cup of coffee and things like that and I’m thinking – what’s going on? Anyway, we got to the College and there was a bus waiting for us. There were a number of people that got on to the bus. I was the only one in a wheelchair, so they made a lift to get me on the bus, different in these days of course, this was 12 years ago. There were a number of sportspeople that were there, high-profile sports people and I’m thinking – whoa, I’m amongst an interesting lot here. “Everyone carried the torch for 400 metres and the bus left St Peter’s and every now and then would stop and one person would get off and it kept going and going through to the University. It was only a few kilometres away, so it wasn’t far. I recall when I got to the Uni that they said okay we’ll get you off now and the ramp, the lift wouldn’t work and they were getting a little toey because the flame burns for 14 minutes, the little gas cylinder in the torch has 14 minutes of gas in it, so if it was to go out, then there are huge logistical problems. So they were getting a little toey, and then we had many of my cousins and people that I knew that were there and they all started calling, singing out “Peter, Peter”, very embarrassing, but funny.

“We eventually got off the bus with not too much time to spare. The fellow who was going to light my torch was a fellow called Wayne Bartholomew, whose nickname was “Rabbit” Bartholomew and he was a surfer, Australian rep. who won, I think three or five world championships. So he wouldn’t have been too far when I got off the bus so there was a bit of logistics to go through very quickly and I couldn’t believe a couple of things. Firstly, they were about four and five deep on the footpath of Sir Fred Schonell Drive and I was just gob smacked. And then the security all around. I said to the one of the guys – I’d like my son who was with me at the time to walk with me if he could. No, no, he said, can’t do that. I said – you’re kidding. No, no, no. And eventually he sort of walked over. I was in the middle of the road and he was on the footpath or the gutter and followed me through. There’s cars and motorcycles you know, police motorcycles and all that escorting everyone through and eventually, so Rabbit came up and lit my flame and I pushed the 400 metres and I must say I did some training before it because I didn’t want to get buggered if there were hills or anything so I did do a bit of training and it was fine. It worked out all right, a little downward slope towards the end and I lit the person’s torch which was some company so it wasn’t only sportspeople, it was people who worked for something like Telstra or whoever the sponsors. Afterwards it was party time.

“It just so happened that my wife’s sister was living out here in Brisbane and she ran the restaurant/cafeteria at the University so it was a simple exercise for everyone in the family to go up to the restaurant and we kind of took over the restaurant and there were so many photos. When I finished the push, everyone’s coming up – photo, can we have photo? Photo please. A lot of them were Asian students etc. They wanted a photo with me and they wanted their own photo and they wanted it with the torch and when we got up to the restaurant, we all had photos taken with the families, uncles, and aunties. A few of them aren’t here with us anymore. It’s only 12 years ago but it was a fantastic day, I must say. I was thrilled to be part of it, still got the torch of course, and looking at the internet yesterday, just doing a little bit of research on the torch, I see they’re still for sale, one of them with the outfit and the torch in a framed thing for $4,500.00 etc. The torch cost $300 to buy and of course you would have bought it. A lot of people had said – well, they should have given them to you, but can you imagine how many torches that would be. I was number 151 that day, and, so if we moved along Coronation Drive to get to the City where they had a celebration of lighting the torch in the city, so I don’t know how many there were. I think Wally Lewis lit the flame in the city that day, or was part of the lighting of the flame. Lovely day, lovely day – it was just one of those days.

“So we’ve still got the torch of course and I sort of made a resolution that day that the torch would never ever be lit again and so the little canister, I think’s been taken out, or probably still in there and I learnt yesterday that the colours were representing fire, flood and sunshine or something like that. So, in the shape of a, sorry for the word “bastardisation” of a boomerang.

(Peter Marsh was interviewed in August and November 2012).

Peter Marsh died November 2012.