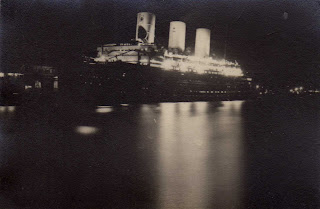

Doug Davis was born in 1918 in Glasgow, Scotland and grew up in Brighton, England. He worked on the Empress of Britain in the 1930s, travelling around the world and joined the Royal Navy during World War II. This is his story:

“In 1937 a friend got me aboard the Empress of Britain as a laundry boy. I was sick as a dog on the first and second night out and I didn’t like eating, even getting up on deck, but the lady who was in charge of the laundry, a Mrs Hills was very kind to me and made sure that I had food and when the sea became calmer, I was able to take my place in the laundry. We were making for the Gulf of St Lawrence and Quebec. When I’d finished that trip, I thought – that’s enough of that and went back to the art school, in 1937 this is. But in May 1938 I joined the Empress of Britain as a telephone operator.

“When I was on the Empress of Britain the city that

impressed me the most was Rio de Janeiro. It had paved streets, wide streets

and generally speaking, was much prettier than the others. Casablanca was a

pretty place, got palms on the quayside. But all ports are very similar, you

know, a few cranes and that, and if you don’t go ashore. In Hong Kong, I met up

with one of the sailors of the submarine Rainbow which was in dry dock

there and he took me up the peak railway in Hong Kong and did the rounds of the

pubs and places and some of the places in Hong Kong were quite English, an

afternoon tea for example. But saw all the sampans though we were docked at the

Empress of Britain, not in Hong Kong but in Kowloon. We had to take a

ferry to get in to Hong Kong.

“I did a series of runs and two West Indies cruises and

the world cruise in 1938/39 where we touched at ports in most important

countries. I had my 21st birthday in Manila and at the end of the world cruise,

I left Empress of Britain in May 1939 and took an interim job in a hotel as

telephonist and timekeeper.

“I was called up into the Navy which was my preference. I

joined the Navy as a rating in January 1940. I remember what cold cold weather

it was going to the holding and training base at Skegness in Lincolnshire. It

was bitterly cold. Well I hadn’t been there more than say three weeks and I

went down with a cold and hundreds of others did because it was a just an

asbestos chalet encampment, no heating at all, a holiday camp and whilst I was

there I hadn’t been much more than kitted up. It caused quite a lot of trouble

for the Navy because it was written about it in the papers. Anyway, I hadn’t

been there more than three weeks and got kitted up and they asked for volunteers

to go and learn what was then a secret mechanism called ASDIC. It was

transmitting a signal underwater to get a reply back in echo. It was

anti-submarine and I went to sea, long before my initial training should have

been over. I went to sea in an old VNW destroyer HMS Wren where they had

ASDIC and joined a convoy about 20 west and came up to Dover. Well when I came

off the destroyer I went with a companion who also came from Skegness and also

strangely enough a Brightonian and we went to HMSOsprey at

Portland and did a full course on ASDIC. I’d finished that about April 1940.

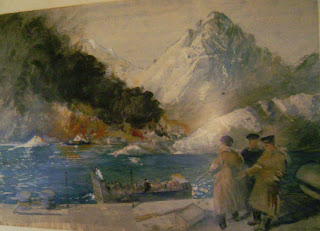

“ASDIC, it’s called sonar now and the Americans took it over eventually and of course they developed it considerably so you can get a picture of what you’re transmitting on. Anyway I went to HMS Osprey and after a few weeks qualified as an ASDIC operator. I was an Ordinary Seaman then at the time and I had to join HMS Tartar at Lyness (in Orkney Isles, Scotland). And I joined Tartar and took my place as an Ordinary Seaman. Tartar was at that time going up to Norway and with other destroyers in the flotilla, protecting shiploads of soldiers landing them to protect the coasts of Norway. We were destroyer flotilla 6 and we took soldiers and landed them at various points from Stavanger up to Molde and other ports in Norway and within a few weeks we had to go and pick them up again. We escorted the troop ships because the Norwegian campaign didn’t turn favourably for the British. Tartar, and other destroyers used to take on fuel at a port from Admiralty tankers at Harstad, way up in northern Norway. During that campaign we went in to deliver some soldiers, to land some soldiers and high ranking officers at a place called Molde and it had just been bombed and all the buildings and warehouses on the quay side were on fire. Well we didn’t stay there too long. We offloaded the soldiers that we were due to, high-ranking they were, colonels and people. Within a few weeks we had to go and pick them up again.

“I was still in the destroyer Tartar when in 1941,

we escorted with other destroyers Q-Force, Princess Beatrix, the Dutch

motor ship and the Queen Emma a Dutch motor ship. They were fitted with

landing craft and we landed the commandos who blew up fish factories, fish oil

tankers and we in Tartar fired the guns at the big ship that was from

Germany that was loading oil, fish oil, and the commandos went and fired all the

different tanks there and I was on Y-gun with the then young Ludovic Kennedy who

became a household name after the War. He was my divisional officer. I was a

rating at the time. I was very friendly with him. We sank many tons of

shipping with our guns and there was a little ship that stood up to us called

the Krebs and we fired at that, blew the bridge off and captain as well,

killed him. There were three or four ships in harbour and some of them wanted

to come back to Britain and help and they did. They had an escort out by us

when we left but we fired at the shipping with our four inch guns and we blew up

a ship called the Hamburg. It was on its way, or nearly on its way back

to Germany and the commandos sacked all the factories and the shipping in the

harbour. Well we picked up volunteers to come back to serve with the British

Navy and that’s about the story of the Lofoten Islands.

“After that, that was 3rd/4th March

1941 and it so happens that I’d been recommended to take officer training

because we had four CW candidates, as they were called, join the ship for six

months and if they got a recommend from the commander of the ship, they would

pass on to King Alfred in Hove for officer training. Well an AFO came up on the

noticeboard. If you are a hostilities only rating, and you have the suitable

educational background, you can apply to be a CW candidate. Well I was

recommended by the commanding officer and I became a CW candidate and I went and

did the training in my home town, which was an added benefit. Well anyway I

scraped through. I got a commission and I passed out about mid-August 1941 and

I volunteered for an overseas posting and strangely enough it was in Freetown,

Sierra Leone, where Q Force were mustered to keep away from the bombing in

Scotland. And Q-Force comprised Queen Emma and Princess Beatrix,

two Dutch ships that had been converted as landing ships with landing craft and

I was to join Queen Emma. Well we went from Freetown in an unseaworthy

boat, the New Northland, which had a list of about 20 degrees as far as

Lagos to join them from Freetown and by that time, they’d gone back to Freetown

so we had to come back again. We got passage in one of our corvettes, the

Armeria and eventually I joined as an officer in the Queen Emma.

“We didn’t do much in the Queen Emma except

exercises with the native Nigerian troops. We did mock landings and in January

1942, that flotilla went back to the UK and they had a toss-up between myself

and the other last one to join officer – who should stay behind with all the old

landing craft and of course it fell to me to be left behind. But it was a

full-time job because I helped with embarkations from the big ships, that

instead of going through the Mediterranean at that time did the long trip down

to South Africa and round. And we did a lot of changing over of troops from one

ship to another because they didn’t put the whole unit in the one ship at

Greenoch (in the Clyde) where convoys assembled or wherever they left and we

changed over these troops into other ships because there’d been a lot of sinking

of ships off the Canary Islands. Anyway we were used in the harbour at Freetown

to do all sorts of things and we lived in the old depot hulk the Edinburgh

Castle which is an accommodation ship and I had quite a lot to do helping

the sea transport officers change over these troops. Then I went down with

malaria because I took some guns up on a landing craft to a place called Jui.

There was a hospital ship in harbour, but they didn’t send me to the hospital

ship because I was friendly with the two surgeons and they were both tropical

medicine trained. So when I got better I continued doing all these troop

embarkations and training of Nigerian troops. They’d climb up scrambling nets,

and they’d make mock landings and so on. So I made valuable use of my time.

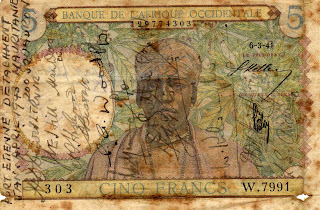

“But then about just after December, I was drafted to a place called Port Etienne on the Cape Blanco Peninsula with a landing craft crew and with two other officers. One was an RAF “bricks and mortar” man, named Barrington, and a couple of big machines that converted sea water to drinking water. And there was a Warrant Officer Royal Engineers came up with us. Well we got these big water purifiers on shore first of all and they were set up. There was a bivouac tent already set up by the RAF and they then were able to fly Hudson bombers to rendezvous with the convoy. There was already an Air France airfield there with a husband and wife at the airfield, in charge of the airfield – Maurice de la Hogue and Madame de la Hogue. There was a big French supply ship called the Jules Verne, with Captain Jalibert as commander and he was in charge of the territory because the territory was a French colony at that time. It was called Port Etienne. The outer half of the peninsula was Rio de Oro French, inboard half Levrier Bay was French and there was a little chain of forts all the way down this peninsula which couldn’t have been more than 10 miles long and about two miles wide.

“They got radar there and they got the planes flying off and rendezvousing with convoys. My landing craft got off everything from aviation spirit, 99 octane stuff for the aircraft and at least half a dozen Hudson aircraft came up to protect the convoy, and there were Sunderlands in the lagoon. Of course I got to know the pilots as we all mess together and toileted together and did whatever we had to do and we knew each other very well.

“We used to go swimming when there were no convoys. But we got a lot of pile drivers, piles to build a jetty, all the aviation spirit from the ship called the Pinto. We dropped that into the sea and my crew got some of the piles, roped them all together, got the 44 gallon drums on to the shore and then they got four ton Crossley lorries, half a dozen of them ashore. We got a fire engine, a petrol bowser, all these things ashore in one small L.C.M. landing craft mechanical and they worked like beavers, they did. That is where I came across Trigg [Lloyd Allan Trigg VC] as one of the pilots. They came up from 200 Squadron RAF they were and they came up from the Gambia, Jeswang aerodrome and it must have been five or six of these aircraft. They were 200 Squadron, Group Captain Constable Roberts was in charge in the Gambia. We didn’t see anything of him but we did some of the big brass of the RAF.

“Trigg was a New Zealander. I wasn’t there when Trigg attacked a U-boat and sank the U-boat and they got him. That was after I left. But I did all the work that was necessary to get a Nissan hut encampment there by offloading everything from corrugated iron to cement, didn’t need sand, it was desert. There wasn’t a blade of grass there at all. From time to time you could see a mirage and we had snow there in Mauritania.

“When I came back from West Africa, I was appointed to an instructional post at RN College Dartmouth which had been taken over by combined operations, the cadets were somewhere else. So we were training Royal Marines (then combined operations). That was from July 1943 to December 1943. We were doing exercises landing American troops at Slapton Beach in Devonshire. As I say I was there in that capacity until Christmas 1943, when I became superfluous because they were moving to the east coast, the whole of the shebang in Dartmouth who’d been training people moved to Burnham-on-Crouch and I didn’t go with them. I was sent to the pool at Westcliffe and from there, I did a bit of training with small landing craft in the Thames. Then I got an appointment to be flotilla officer of landing craft at Calshot in Southampton. It was an auxiliary flotilla. They were building up for D-Day. This is 1944 of course. The harbour was full of American ships and American troops for D-Day. I had this ancillary flotilla and didn’t go. We were sent down to a place called Tamerton Foliot in Devonshire to await any casualties and crew and go the second run. I didn’t go over on D-Day at all. So I was lucky in that respect, or unlucky.

“Then when D-Day was over, we were sent on a commanding officer course for major landing craft and we spent a couple of months up there in the Clyde, training for major landing craft mainly out at sea, manoeuvring and navigating. Well that packed up, but we got our commanding officer tickets and we were sent back to Brighton, Lancing actually for change-over training to general service. After I finished that general service, I joined a corvette call Amaranthus and I was First Lieutenant of Amaranthus and we did a run from Gibraltar, Casablanca, Dakar, Freetown, Takoradi, Lagos and then did the return journey. We were most of the time convoying French ships full of French troops, changing the garrison on these various places. So we did a fairly valuable job there but we escorted convoys and we escorted with the help of five tugs and as many ships as they could get, including armed trawlers. The old Asturius had been torpedoed. Eventually after about seven weeks of running up from Freetown with the crippled Asturius we got it in to Gibraltar. Well it subsequently set fire and it wasted all the effort of the tugs. The big tugs were ocean going Dutch tugs, the Thames and the Schwarzsee. But after a few weeks, somebody set the thing on fire and we lost the Asturius. After that we did patrols and Amaranthus was decommissioned it in Chatham in July 1945.”

(Doug Davis was interviewed in September 2012).

Doug Davis died in 2015.