William Hatfield was born in January 1939 in Bridport, Dorset, England and arrived in Australia at the age of three months. In early 2020 Bill Hatfield succeeded in being the oldest person to sail around the world unassisted. This is his story:

“We arrived in Perth which I knew nothing about. I was too young. And then we came over to Sydney and my first recollections were at about the age of four in Sydney. War was on. There had been an attack on some ships in Sydney Harbour from a Japanese submarine and my father who was in the Army thought that there was a possibility of a Japanese bombing or invasion of Sydney and so we moved to the Blue Mountains at Wentworth Falls. That was my earliest recollection. My father was in the Citizens Military Force at Dubbo and he caught bronchitis. He thought he was going to die and it was recommended that he be discharged from the Army. We then moved up to Green Island and that was a most magnificent time. I remember the absolute joy of getting on this little tramp steamer in Sydney Harbour and seeing the pilot being taken off the ship in rowboat, two men in a rowboat over to the pilot ship, Captain Cook and heading north in this little tramp steamer.

“Wonderful time. It had a little two-pound gun mounted on the stern for anti-submarine warfare and my sister and I used to get on this. I’d operate the travers and she’d operate the vertical elevation. And we used to line-up passing aircraft when we could and try to shoot them down. We were very disappointed when we’d seen we’d become experts at this little gun. Anyhow we arrived at Rockhampton going past of all places, Lady Musgrave Island, which was the first coral reef island I’d ever seen, at the age of five at the time. Then a slow goods train, mixed train up to Cairns and over to Green Island shortly afterwards. So that was my first introduction to the sea.

“My father, said, when I’m better I’ll teach you how to swim and then once you can swim, I’ll buy you a boat. So my sister and I rushed up to the camp site one morning and said, hey Daddy we can swim. So he saw that and said, yep. My sister learnt to swim breaststroke and I swam under water because it’s the fastest way to swim. I didn’t learn to swim on the surface until I was about 12. So he bought the family a 12 foot dinghy and he taught me to row in that. I used to take great joy rowing with my father over to the wharf to pick up our week’s supplies and row back with father sitting in the back. I had free run of the boat at the age of six and I actually rowed round Green Island at that age. So that was my introduction to the sea. Absolutely charmed by it. And the War ended when we were on the island. That was August of course, ’45 and we left in about January ’46.

“They said, we’re doing it for your children’s education. We said, we’re happy to be here, be happy. We don’t need an education. We wanted to stay on Green Island but in fact, we’d been kicked out because it was a Reserve. So we then went down to the Hawkesbury River and again, little bit adventurous. I borrowed somebody’s boat which I shouldn’t’ve and got into it, slight amount of trouble. So my father built a 12 foot dinghy within the year and I used to row around in that. Then with the strong north-westerly blowing, I rowed for ages up to the north-west and stand up in the bow with a sugar bag, or chaff bag and pretend I was sailing like a square rigger. So again soon after that, my father got a masted sail I used to sail around on this boat. I thought that was absolutely wonderful though not quite as good as Green Island but pretty good.

“Again, supposedly for our education, we moved to Sydney. In fact it was more my mother working, my father working in Sydney. Very soon after we moved there, I got a weekend job with a boatyard and so I was around boats all my early life. At about that time, I wasn’t allowed to row at school. My father, was sort of against team sports. I went to Sydney Boys High and on the rowing machine, I was strong and I could have rowed I guess in the high school team but did not. I joined the University of NSW Boat Club and spent many wasted years rowing from 1956 to ’64. So again a lot of water and then I graduated in Civil Engineering by this time, rowed in a lot of inter-varsities. I think it’s twice I won the inter-varsity sculls and in that period I also failed university, twice, became the Australian Single sculling champion, won a coxless four and rowed for Australia in the Empire Games, and then I had to start work.

“The Empire Games in 1962 was a little bit of a schmozzle. Maurice Grace and Peter Raper represented Australia in the 1956 Melbourne Olympics and then Maurice Grace and I teamed up against Peter Raper and um, [not sure of name] and we used to race against each other in pairs. We were the predominant pair at the time. We won two NSW championships, (name will come to me) and I. And in the selection trials Peter Raper beat us but we used to team up in a coxless four and we were unbeaten in the coxless four, every time we raced and won the selection.

“When we got to Perth, there was an attempt to have the two Victorian reserves row so they said – your four is being disbanded, the Peter Raper and Maurice Grace the Olympians are going to be kicked out and you are to row with the two Victorians. And I said – they’re not my crew. They said – well if you don’t row with them, you’ll be kicked out of the Empire Games. I said, well if that’s the case, so be it. And then they decided that they wouldn’t kick out Maurice and Peter. They would row in the coxless four and I rowed in a pair with Roger Ninham. So it wasn’t such a good crew.

“Roger had won the single sculls, same as I had. So we never ever trained in the coxless four but we were both, groups of us skilled pair oar rowers and we could easily beat anybody in Australia at that time, with hardly raising a sweat because coxless fours were not the racing boat at the time. It was mainly coxed fours and coxed eights. So when we got in this boat, we rowed it again without a rudder. I was up in the bow seat and I could just say bow side stroke side together and so we didn’t have a rudder dragging us back. So that was the rowing, and then we were told of course that nobody would be selected for the Rome Olympics, no sculler because Sam Mackenzie was rowing in England at the time and he is going to be the sculler. So I joined with another guy in a double scull. We didn’t do so well and then after the ’62 Empire Games, then ’64, I think it was Tokyo I joined up with Ian Tutty. Unfortunately, about three months before the trials, I had a motor scooter accident and lost my finger and broke my wrist and dislocated my shoulder so that put me out of the boat for about two weeks and we didn’t quite make it. I wasn’t really fit enough. So that was the end of my rowing career. Until, and then, as I say I was an engineer by that time, went round the country at various places, New Guinea, mostly New Guinea and Queensland. And was an engineer until I was 35 or so.

“My marital status, we’ll I’m officially engaged. I met Barbara in Bundaberg and I had a yacht at that stage and as I said, we moved down to Brisbane. I with the company and Barbara was a nurse and so I said, look I want to go sailing now. She said, I’ll come with you. I said it won’t be much fun, it’s only a 24 footer. She said, oh that’ll be okay. So she and I set out for Lord Howe and Norfolk and continued on to Whangarei, New Zealand, and Rapa, Pitcairn Island, Easter Island. I said we’ll go to Peru but we met the commander of the Chilean navy in Robinson Crusoe Island. And he said, come be a guest of navy in Valparaise and he had been the commander of the square-rigged bark, Esmerelda and he said, why don’t you go around Cape Horn? I said, well fair enough. So Barbara and I went round there. We lost our rudder off the boat just after Cape Horn. So struggled in to the Falkland Islands, spent six months there until a rudder came from Australia and then continued up River Plate, Montevideo, Rio, the Amazon, the West Indies, through Panama, Cocos Island and fabulous month on Cocos Island. That’s the island that features in Jurassic Park, beautiful, unbelievable island and Barbara notified me that she was pregnant. So we then continued back to Easter Island to see friends there, back to Pitcairn, up to the Marquesas, Tahiti, Suvarov Island, a beautiful atoll of the Cooks and we had a little bit of a false alarm. Barbara was seven months pregnant by then and so we got to Fiji and that’s when my first daughter, Katherine, was born in Fiji, and we sailed home from there. So, was I married? Well I’m engaged, because I said to Barbara, will you marry me and she said yes. I said, when will that be – and I’m still waiting. So that’s Barbara. We then had another daughter, Helen.

“Katherine, and Helen. And I got a fishing boat, aluminium fishing boat and we were going to fish as a family. We started off there and, out of Bundaberg and then a cyclone came and dramatically we got wrecked in 85 knot winds, rapid reef, Swains Reef. Couldn’t pull the dinghy in because the wind was too strong. We had an inflatable life raft. We couldn’t get into the boat because of wind so we ferried the girls over, one at a time. The boat was up on the reef, sort of swamped and on its side.

“And then as I went back to untie the boat, the painter snapped and I tried to swim after them but I got tangled up in fishing lines and, they were around my feet and fast disappearing over the reef. So I pulled a 10 foot dinghy off the top of the boat, um, then got into that and it was swamped, of course, in this wind and set off and some four or five hours later, I think, I spotted a life raft. So I swam over to it. It was upside down and I’m trying to right it and Barbara and the two girls came out and I said – the children are dead are they? And she said, oh no, they’re all right, ‘cause they’d closed their eyes as babies do. Helen was 15 months and Katie was 2½ . So we righted the life-raft, got back in again and a couple of days later we were, that was Saturday, I think, and Sunday a plane spotted us and Monday morning they dropped us a life-raft, another life-raft and we got into that which had a radio and water. And food, we had no food or water on the life-raft. It had gone missing. Got on to the boat, and, got on to this Japanese Coal carrier and I went to Newcastle.

“Then we decided to build a wooden boat and, a 40 foot wooden boat, myself and a boat builder, built this and Barbara surprisingly enough wasn’t too keen on coming fishing with me. So, I then fished thereafter with a crew as the girls grew up. I fished and Barbara continued her nursing and that’s how it went. Girls left home. Eventually I sold the fishing boat when I was 70 I think and then Barbara stayed in Bundaberg looking after her lovely, my mother-in-law until she died at a nice old age, well in to her 90s. And I said to my older daughter Katie, don’t not have children to advance your career because having children is a marvellous thing. And I said, look, if you have a baby, I’ll be Grandpa so three months later she said, were you serious? And I said, yep. She said – that’s good ’cause I’m pregnant. So I looked after my grandson Constantine. Katie had six months of maternity leave from the government and then I looked after Constantine from the age of six months to 3½. I used to take him in and have him breast-fed at lunchtime and bottled breast milk, mornings and afternoons. I did that for about 3 ½ years. And they went off skiing to Canada. I had already been as a Nanny to Charlotte’s Pass and to Japan, looked after very well and that was getting to the stage where Constantine was sort of going to a lot of day care and they said well what are you going to do Dad. I said, I don’t quite know. So they said don’t do anything silly while we’re away. So I went and bought a yacht.

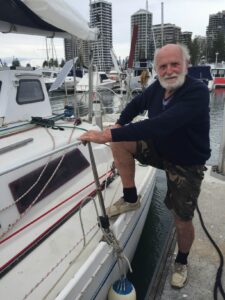

“And so I bought a yacht in Hobart. It was called “Reflections”, a 33 footer. Sailed it back up with some mates and friends to Brisbane and thought I’d do some long-distance sailing and that’s when I discovered that there was a record which had yet to be set, a west-about non-stop navigation in a boat under 40 feet. I thought, oh well, I’ll try that. I set off in 2015 and had a reasonable trip across the Indian Ocean, lost a forestay, fixed that, almost a head sail and up round the Azores. I left from Sydney, up around the Azores in the North Atlantic, then passed my old stamping ground of the Falkland Islands, went round Cape Horn. It had been blowing quite strongly, definitely around the 50 knot mark.

“I’ve got the dates. [2015 started, 21/03/2016 Cape Horn] As I say, I’ve had a few trips,

“I left in, I think it was August or was September 2015 and went round Cape Horn in 2016. Right and that’s when it was blowing about 50 knots, quite strong, quite rough and then it eased off to about 35 knots and the wind round a bit to the south, to the west, slightly southwest. I said I could change tack to head up north and a sort of sudden wave came up, capsized the boat and sent me into the water. I managed to get on ’cause it was not totally upside down but pretty close to it and I got over the rail and gradually the sail came up and I noticed that a lot of the rigging had been damaged. Um, so I pulled down the mainsail and just sailed with the headsail back to the Falklands. I’d lost all my radio, my motor, most of my navigation gear and my satellite communication gear. It was all swamped and so, it took me about 10 days I think, something like that and sailed into the Falklands and sold “Katherine Ann” there. I was going to take the gear that hadn’t been swamped off it and I was offered a reasonable amount of money for this pretty well wrecked boat and I flew back to Australia.

“As soon as I got back, well, I shouldn’t say ‘as soon as I got back’. I was in Auckland airport with free Wi-Fi and found a steel boat in Melbourne. So a short time after I arrived back in Australia, I went down to Melbourne, actually nearly bought it and till the survey was being done and I realised that most of the boat was a wreck.

“One of my good gliding friends, Hank Kaufmann was a boat designer and I said to Hank – what’s your best boat? And he said Northshore 38 and I said, well there’s one for sale in Cairns, would you like to come up and have a look at it? So we flew up there. He said – yep, it’s sound, little bit of toing and froing and a little while later, we flew up again, inspected it thoroughly and I bought it in Cairns, sailed it back down to Brisbane. My daughter, Katherine, flew up to Hamilton Island with my grandson aged about seven I think at the time and the wind came up, bit of gusty wind and Katie said – is it all right? It was heeling a fair bit. Constantine was asked to stay downstairs. He was enjoying it and Katherine’s hanging on. The boat heeled quite a bit, too much sail up and she said – what speed was the wind when you were capsized around Cape Horn, Dad? I said – oh about 35 knots. She said – what’s it blowing now? I said – about 35. So we were going to go outside, so we had a nice sail round there and Katie flew back, mate came back and joined me and sailed on to Brisbane. So that was, got ready to set off for the record again.

“So not long after that, um, I headed off, had a bit of trouble, sailed round the bottom of Tasmania. Actually a double start, sailed down to about Bass Strait, fair bit of damage, sailed back to Sydney, boat got fixed, sailed round to about across the Great Australian Bight where I encountered a significant storm, [storm in Bight 29/09/2016] to just past Albany, some more sail rigging damage, steering damage, sailed into Albany, back to Hobart and back up to Brisbane.

“So then I set off again, in the same boat, “L’eau Commotion”. And then I left Brisbane and had a reasonably successful sail until I had a forestay, went, I lost the forestay near Madagascar, continued on to some calm weather outside the Cape of Good Hope and Capetown. Fixed it up there, sailed up. I left from Brisbane, sailed round Canary Islands. This is to make the official distance. Then continued on round Cape Horn and again having a little bit of rigging fraying. So I sailed back to a bay, called Baiha Espanol, I think, a bay near Cape Horn. Used an anchor chain as a, one of the rigging stays set off, within an hour or so that chain broke, sailed back to Espanolo, put some more rigging in and set off for Australia with only head sails and the boom was not operative under the mainsail.

“So that took me, oh, three or four weeks I was down to the latitude of Antarctica, about 64 south, about 600 miles south of Cape Horn and then tried to go against the westerlies without much luck. And then I had a further capsize. I lost my solar panels, windmill. My steering went and so I thought – enough’s enough. Sailed back to the Falklands, pretty uneventful trip. Got new rigging and new electrics and sailed from the Falklands across the Pacific non-stop back to Brisbane. Um, about September and would have been 2018. [10 September 2018] And I thought – get going early but I couldn’t get the rigging properly replaced. The rigging wasn’t so good that I made in the Falklands and so I was going to sail straight away but I was going to go about Christmas but couldn’t get ready and so I was ready to sail in June 2019.

“So I left 8th June 2019 and had a fairly uneventful trip. I had some wonderful double head sails and making wonderful time sailing up past St. Helena and towards Ascension and I noticed the speed suddenly dropped down to, from 8 knots to 4 knots. And I looked ahead and this double headsail had parted and it was billowing out in front of the boat, partly in the water. And it’s like a spinnaker and I tried to pull it in but the wind was blowing, a lovely trade wind, about 18-20 knots, couldn’t do that so I went back aft and I wasn’t strapped on by the way. And put the tiller hard over, stopped the boat and pulling in the sail and little bit of a slop and the sail caught under my feet and lifted me over into the water. Fortunately, the boat was stopped. Interesting bit of psychology – the boat was dead stopped in the water. I kicked the sail, it was wrapped round my foot and instead of swimming round to the stern, I felt my way like a kiddy, like I’d taught Constantine to do in a pool, like that. I was stretching my arms, the boat was rolling. I just didn’t want to let go of the boat, so all in the brain, you know. If I had any sense, I would have let go, swum round the back. Anyhow I got the sail in, set up other sails, headed round the Canaries, again some islands I’d been through before, back down, occasional strong weather, nothing spectacular, up the coast of Chile.

“No problems going through the Horn this time, none at all, no just all very straight forward. Occasional strong winds, you know reef down hard, 30 or 40 knots, this sort of thing but, what I did, totally furled my two head sails, totally furled them, put the boom out to the side and double reefed and found that was an excellent way of handling strong weather because sails didn’t flap. There’s no chance of being knocked and going about. And, so there was a little bit of strong weather, but very comfortable. I just set an offshore course, very alert on an onshore course and relaxed on offshore course and occasional strong winds. Oh, and I’d lost my two self-steering rudders. They had failed, the electrics. I had no electric autopilot. My manual autopilot I lost the main autopilot rudder round, as coming past Cape of Good Hope, bit of strong wind, the boat got tipped down a bit. And I was running under autopilot. It only failed when I got towards the Canaries. So I had a spare paddle for the wind pilot, put that on. It broke again near the Falklands so I pulled up and sort of plywood furniture and made a paddle out of that. It broke again, I made another one. But you know these are things that are just part of day-to-day life when going along. So, that paddle then lasted all across the Pacific. Had good run, pretty good trade winds. I think three cyclones with right in the middle of the cyclone season so January in the south Pacific but they were all well away, you know. I didn’t make any course alterations, kept going. Said to myself, I’ll work out what to do if they come close but they were just, you know, I don’t think they got closer, hundreds and hundreds of miles. And I had a really good run into Brisbane, and that was it.”

That was it! (Laughs) Yes, that was it. I think we need to unpack it a bit more. It’s a bit more than just – that was it, isn’t it? Can you tell me why it was important that you sailed west rather than east?

“Well, only about five people have circumnavigated the world going westwards, nonstop and nobody had done it in a boat under 40 feet. So there was a world record to be had. So to get a world record, you have to go to record keeping which is the World Sail Speed Record Council and you have to apply, state your course and then you have to have a recording device to show your position every four hours and you have to report going round the turning points. So to do the circumnavigation, you have to do a great circle course of 21,600 miles, that’s 60 nautical miles x 360 degrees. Where we are in the southern hemisphere, you can go round, cross every meridian but you don’t actually have to go more than about 14,000 miles. So they say you’ve got to actually pick a land mass or a navigator fixed beacon such that your course equals that 21,000 miles. So I looked up and, like a bit of internet navigation, calculated where a point would be and the island of Hierro in the Canaries just made it by only a very short margin and so I sailed round that, so achieved minimum distance. Some people say – well you can go up to the Equator and count as a circumnavigation, which it is, but not according to the record keepers. So that’s why I had to go there and so I applied for the record. My navigation system sent out a position every two hours, which is recorded on the net. And I notified when I went round, there’s only one point that I had to notify and that was Hierro and well, I did notify Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn in case I went back the other way. And so then I got the official record for the initial record for a westabout under 40 feet. They don’t count age with a world speed record council but in the Guinness Book of Records I’m also the oldest. A few people have tried the record but they’d had problems and so it still stands after 18 months.

“A lot of the time you get on a tack and sail quickly on trade winds and you might have the same sails up for days or week at a time but you’re always looking for where the winds are likely to be and what is best track so you spend a lot of time on that. I had a wind program and that would give you the forecast wind for how long you’d like to dial up for it – a day, three days, seven days, about seven. It goes to 14 but anything over seven days is a pure guess. So you look at the winds a lot and say, where am I going to go, which side of the course will I go? Where will I change track? So you spend a lot of time just musing over this, into this satellite pictures that show all the details you want to know. And then I wrote a Blog every day. It takes a little while, you know, it takes five minutes to read it but lot longer to put it together. So I did that, and not much else, you know. I didn’t have news. I sort of purposely didn’t try to get the news. You can get a bit obsessed. I was reading a lot in one of the earlier trips about the Boko Haram I think in Nigeria or wherever it was, you know, and I thought – oh gosh you know. So after that I didn’t hear the news except little bits that Katherine would pass on to me. And so I virtually did nothing. I had King James Bible on my iPad. I had the, quite a bit on the theory of relativity. I had Charles Darwin Voyage of the Beagle, all of interest to me and so I spent a lot of time looking at the information I had on the iPad, not reading novels so much, but things that I’m interested in.

“You asked what does one have to do to be a ‘Cape Horner’. Well people travel round, going back, in about in the 1930s, it was just about the last of the sailing ships so they got a group of masters who had sailed a ship around Cape Horn and they said – seeing that we’re a dying breed, age of sails gone, we’ll form an association of people and reminisce about Cape Horn. So they formed themselves an association of Cape Horners, of people who had sailed around Cape Horn in a square rigger ship. And, after World War II, we had a ship called the “Pamir”, and it was running wheat from Adelaide to England. The last grain race, and there were actually a couple of ships that set off at different times.

“Then they decided – well there’s going to be no more square riggers, what about people who sailed round Cape Horn. We’ll form an association of people and we’ll make a rule that they’ve got to travel from, as I say, from 50 south to 50 south without motor or outside assistance. You can be a crew, right, but you have to sail and without dropping in anywhere. So they formed this association and I’m proud to say that a patron of the Cape Horn was HRH Duke of Edinburgh, Phil the Greek, as he’s more commonly known or one of the Hapsburgs. Right, I shook hands with the man who gave me a bronze medal in Perth in ’62 and he also was until recently the patron of the Cape Horners Association. So I got a note to say that yes, I’ve been accepted as a member of the Cape Horners. So that’s what I have a little newsletter, cost me 50 quid for two years. Anyhow I’ll keep that going ’cause I haven’t got much longer. Anyhow that’s the Cape Horners.

“The rules for the circumnavigation – you have to start from a definite transit point between two landmarks. You have to come back to that. You can get no outside help and supplies or anything else like that. You have to travel a fixed distance on the great circle and I actually travelled about 30,000 miles as against the 21,600 you have to. And you’ve got to report in and you’ve got to have a trained observer to see you off and get back. So that’s the rules, quite extensive.

“An incident that happened when I was going across the Great Australian Bight and I had an AIS, Automatic Identification System. And it has an aerial on the mast and it puts out a signal which travels perhaps 30 miles. And it can receive signals from boats about, way over the horizon. So you get an AIS recording of the other boat, its heading and speed, first off. As it gets closer you get its heading, its speed, its length, beam, draft, speed, course. Ah, next port of call and estimated time of next port of call. Everything. Your boat tells you the same but, except mine only tells me sailing yacht, 12 metres, ah, speed and heading, righto. Mine’s a start Class 2. So I saw this ship from miles out and I’ve got a transponder and it’s only fairly low, about 10 feet above sea level. See, I’m old, 3 metres. You know what 10 feet is and it gets the radar and goes in and spits out a return. So it gives a radar reflection, doesn’t say anything, just says bip at about nine miles, or eight miles. Still out of sight or line of sight but you can’t actually see it. So this container ship, and you get a calculation and you can see that we would intercept in a few minutes time. Our courses were converging. So I’d been looking at this guy for about an hour or so, see’em bip. Yeh, make sure I don’t fall asleep and then I called him up by his name, Greenpacker or whatever, um, this is sailing yacht “L’Eau Commotion”, we appear to be on converging courses. Shall I alter my course to starboard. Well, shall I alter my course, but I couldn’t because the wind was coming there. I couldn’t go much this way or I’ll have to go around and turn back. But you don’t do that because his calculations are all this, right. You didn’t know what you’re going to do. So he said – that’s all right sir. I will alter course to starboard by 10 degrees and I will pass you one mile, which he did.

“That was particularly nice because it was a huge container ship, 400 foot long, and that’s the reply. That’s the response you get from these guys. They can see who you are, get your good radar reflection, they will go around you because you’re sail, right? And if they know it, they are obliged to do it, okay. If you don’t have this equipment aboard, they could say – well I didn’t see him. Because they can’t see you. It can get rough in the Bight but there are often big swells, okay. And your hull and half your mast will be down inside a big swell and only popping up now and again and if that scanner’s looking that way and also with the breaking waves which are quite often not serious but it will give a reflection so they’ll look out over the top of the reflection and cancel out anything within a short distance so they’ll never see you. But I say with the AIS and the transponder, the two go together, even though they’re quite separate you’re pretty well guaranteed no one will run you over. So yeh I think you’ve got these marvellous systems and of course, you’ve got the GPS now so you can dodge islands.

“Food was very basic, very basic, starting off, a few oranges. I had a fridge for about two weeks before, packed it in and had a little bit of steak and a few vegetables, that sort of thing but then basically I went on the real basics – tinned salmon from Aldi, very cheap; dates from Aldi, very cheap $1.60 and $3.00 a kg; rolled oats, flour for pancakes; dried egg powder; peanut butter.

“No chocolate, no sweets. Few tins of golden syrup which I never, occasionally a light smear. No I don’t like sugar and yeh very basic, what else did I eat? Caught a few fish on the way. Flying fish are lovely on the deck fried in olive oil, lovely. You can, except for the bigger ones, you’ve got to scale. The small ones you can crunch away, lovely. Dorado small fish, occasionally tuna, but not a lot. Tinned beans, right, I didn’t use whole because of the problem, possibly problem with water I used the actual cooked red kidney beans which I love. And, with beans you’ve got to wash them and then you’ve got to boil them for a good whatever to poisons are in them. So I said I won’t bother about that in case I get desperate, don’t have water and so had tinned beans. So that was it. Tinned beans, tinned fish, no prepacked meals.

“I had a couple of fruit cakes. Would you like to see my ecologically friendly Christmas cake? Birthday cake? I hooked up a solar panel and a 12 volt light bulb and put that in and blew that out so that I can’t pollute the planet with candles. Fruit cake, someone made me a fruitcake for Christmas and one for my birthday, yep. But that was it, just the two. No biscuits, no Saos, no Tim Tams. Yeh, very very basic. Generally, we eat too much meat. The amount of protein you need is, I think 60 grams. So I set out to eat 60 grams of protein. And you’ve got brown rice. You’ve got, I don’t know, 6 or 10% protein in oats in a little bit rice, you’ve got a certain amount of fats in oats, less in rice. So I’ve calculated the amount of protein taking the flour and whatever one, two, three flour’s the worst. Ah, and calculated 60 grams of protein, so much carbohydrate, so much fat, on a 2,300 calorie diet. Vitamin C, I found out that, I don’t know how much an orange has got, 10 or 12 milligrams, but you can’t keep oranges for very long. They did a study in World War II against conscientious objectors and they found that about 6 mgs of Vitamin C will prevent scurvy per week. It’s extraordinarily small. So I just took a Vitamin pill every day, quite strong 60 mgs or something like that so that solved the scurvy problem, which you get at, I don’t know, three or four months of no fruit or fresh vegetables. In the Falklands a guy showed me a scurvy grass there, chop them, out in the open and we were waiting for some info and he showed me how to find scurvy grass. It was snowing at the time and he showed me how to make little fire out of the weed, you know. Yeh, you can just eat any grass or any succulent and you’ll get enough Vitamin C. So, yeh, Vitamin C covers brown rice, oats and tinned fish. That was so very very basic.

“I had lots of milk powder, little cheaper than $1 a litre and you know excellent food. Fair bit of cocoa sometimes got mixed up with egg powder, cocoa, dried milk powder and you know sort of, say eat well and I did for the first so many months, live on milk even though the purists say, you know, cow’s milk is good for baby cows. I’m a believer that it’s a total food. It’s got the sugars, the fats the lot. So I calculated that a litre of milk a day and, of course, as I liked it so much sometimes I’d mix a bit more, so I always had a bit more milk than I actually needed. Dried milk is, to me, a perfect food, along with dates and cocoa, lots of brewed coffee. I gave away smoking when I was 30, fifty years ago and I gave away drinking thirty years ago but never got to giving away coffee. And if you read the right people, and ignore the rest, they’ll tell you it’s good for you. So lots of coffee.

“I do Blog. In the last trip, I did it every day and just before 6 o’clock in the morning Australian time. Sometimes late at night and sometimes it was middle of the day but, every day. I did that as sort of safety measure because if I didn’t put it in, which I had done a couple of occasions in the past and people got back to me. That’s not enough to get a rescue but had I been in trouble, I’ve got a few EPERBs which give you GPS transmission through the satellites and if they saw no Blog, no movement, but a GPS going out, I’d have a few people saying, ringing up and saying – yes, that looks a bit suspicious. So that was one of the reasons, plus it was fun to write.

“I had two desalinators, one was electric and one was manual in case the electric one failed. In my first trip on “Katherine Ann”, I had solar panels with a gutter around them and if it rained, I’d take a lot of water. But amazingly, you can travel thousands of miles in the tropics and not have a shower. It’s hard to believe, you know, through the Doldrums down the coast, As I ran out of water, rainwater from collecting it on “Katherine Ann” so I got a $300 disposal non-guaranteed hand pump which made about three to four litres an hour with this hand pump. It’s very light. It’s not an effort but you’ve got to be terribly regular and of course, the boat’s always moving and if you got kicked off your feet a bit, it would stop functioning. Even though it’s manual, the click valves and then you had to pull the water out and then pump for five minutes to get the salt going and put it in again. So I had one of these as a spare on the last two trips but I had an electric desalinator and it puts out about four to five litres an hour. The more the water the more desalination you get and it would run off solar panels or subsequently I had a trailing, not a trailing but sort of like an outboard motor, a generator, so I could get solar panels which were wiped out on another occasion.

“I had a welcoming party when I returned to the Gold Coast. One of my dear gliding friends Kerrie Claffey, Tom Claffey I’ve raced against. Kerrie’s not such a good glider pilot but Tom is an Australian champion. I think he won a world championship as a very good glider pilot. And one of my other glider pilots said – ask Kerrie up, when I had my original boat. Kerrie and I would have gone back a long way. I’ve sailed with her and all that sort of thing. So she said – look, I’ll organise a bit of a welcome for you. So she rang up a few people, said we’ve got a world record. So that welcome home was all Kerrie’s doing and you know, it’s much appreciated.

“To have a boat going overseas it has to have an official number. This boat never had it so what you have to do is go back through the history of all the owners of the boat from the manufacturer to see that it’s been legally passed on. So anyhow here’s this boat the “L’eau Commotion” and I thought, will I call it “Katherine Ann” or, cause “Katherine Ann” had gone off the registry as my other boat had because I’d sold it overseas. And I thought how hard is it going to be, and it was very difficult. Talked to a bloke in Sydney who was an owner and he gave me a little bit of information and then said – I don’t think I should be talking to you any more, goodbye. So I eventually got the boat registered, official number. I had to pull into Sydney cause of that bit of trouble round Bass Strait. The Cruising Yacht Club of Australia, and the bloke I bought it from said, I like the boat, it’s a funny sort of name. He told me, that when he bought the boat he said – I like the boat, funny sort of name. The bloke said – humph, well I named it. This bloke’s walking down the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia and his wife or girlfriend says – oh John, this is your old boat. And he said – humpf yes, and she said – you like this one better than the one you’ve got now don’t you? And he said – yeh, yeh, yeh. That’s right. He’d bought a later model and he had named it “Loco”. It was oh, some other name, “Raptor” I think, right and he’d changed the name so the bloke who said – nice boat, dreadful name. Laughs. I spoke to him and said – nice boat, better than the one I got. Yeh, so that’s the story of “L’eau Commotion”. Ah, and apparently it is a French word.

“Water and commotion, commotion (French) right is actually white water, like a rapids in French. It’s actually really French, even though it sounds a bit corny. “L’eau Commotion”. So that’s where “L’eau Commotion” comes from. The bloke named it that.”

[Citation from Sailworld – 22 February 2020 Bill Hatfield became the oldest man to sail around the world solo and non-stop. Also the oldest man to circumnavigate the world solo non-stop unassisted at age 81. He’s now secured two official records regardless of age as confirmed by the World Sailing Speed Record Council on 11 March 2020. Sailing from the 8th June 2019 to 22nd February 2020.]

Bill Hatfield was interviewed in May 2021.

See a YouTube video of an interview by Cruising Connoisseurs’ Mark Philpott with Bill Hatfield before Bill left on his journey here.

Read a report on Bill Hatfield’s achievement on ABC News here.

See a YouTube video created to encourage Bill to “Bring It On Home!” here.

See the Channel 7 news report of the day Bill arrived home here.

See Bill Hatfield’s Blog of his sail around the world here.