Erika Redgrove was born in January 1941 in Eastern Europe and arrived in Australia with her family as an eight-year-old refugee in 1949. She won a scholarship to attend the University of Sydney and became a Secondary School teacher of English and German, teaching both in NSW and in the U.K. Her last stint as a teacher was at Richmond High School in the Hawkesbury district, where some of her students became lifelong friends. This is her story:

Erika was born Romualda Dulimov. She explains:

“I was christened Romualda. I don’t know where that name came from. I can only surmise that my mother named me after a relative or a good friend. When we arrived in Germany, we had to fit in with the German people and as Erika was a popular German name, I was renamed Erika. The German spelling is with a ‘K’. It was not a popular name in Australia at that time”.

Erika spent her childhood in Germany after her family fled eastern Europe.

“I remember very little of our flight westwards through Russia, Ukraine and Poland as I was only three years old when we arrived in Hann-Münden, a beautiful little town located just below Hannover. It is famous for its three rivers, its over six-hundred-year-old decorated timber houses and its surrounding forests. The war had not yet ended. We were allocated two rooms in the attic of a two storied house. There was very little food available. We were given a sack of potatoes and a sack of oats. That was the only food we had apart from the few vegetables my father was allowed to grow on the allotment of land next to the Fulda (river).

“The very first memory I have of Germany is the day when my parents walked down to our allotment next to the river. I was in a pram. It was a hot day and as I was so very thirsty, I said: ‘Mama, ja hachu piet,’ meaning: ‘Mum, I would like a drink.’ My father was standing in front of me and my mother was beside the pram. My father screamed at me that I must never speak Russian again while we were in Germany. I was only to speak in German. As I didn’t know a single word in German and as I had never been screamed at before, I was very frightened and did not speak at all for a very long time, until eventually I learnt some German.

“We had to fit in. I did not know that my parents at that time were terrified of being sent back to Russia. I also remember being told that when we were in the attic, we had to speak softly and tread quietly so that no one had grounds for complaints against us. We were lucky that we had been given accommodation in that rather nice house at No.5 Schröder Street.

“I was happy in Hann-Münden because we weren’t running and running. I was no longer enveloped in fear as I had been when we were fleeing through war-torn countries. We had a place to stay and we had some food. Sometimes our oats and our potatoes were supplemented with tomatoes, cucumbers or radishes from our allotment. We weren’t made to feel different or seen as foreigners. We were just accepted.

“I started school at age six. I couldn’t speak much German. My teacher, Fräulein Fernau, was so kind and took pity on me. She stayed back after school to give me extra time with her. Even after we immigrated to Australia, she got the class to write to me every year and sent me books to read. That’s how I kept up my German for years. There were about 40 of us in the class. I was amazed by how well they could read or recite poems fluently, whereas I could hardly say a word.”

“In September 1945, the war was over. Germany had been partitioned into four zones by the victorious Allies. Hann-Münden was now in the British Zone. My father worked in the nearby Schrőder factory where he heard from some other workers that the next day all prisoners in camps, as well as refugees and displaced persons of Russian, Ukrainian or Polish origin who had fled to Germany were going to be sent back to Russia by British soldiers, as per the Yalta Agreement.

“The British camp was not far from where we lived. My parents were terrified we would be sent back and that our whole family would be killed as my father had fought against the Communists. Although there was a curfew, you were not allowed to be on the road after six. There were signs everywhere which said, “Curfew – beware, you may be shot if you’re found on the streets after six o’clock.” Nevertheless, my parents took the risk and ran to the British camp and asked to see the Commandant.

“It so happened that when we had fled through Poland, we had ended up in a camp in Litzmannstadt. There we had applied for and obtained German nationality because of my mother’s German lineage. My mother showed the Commandant our citizenship papers and the statement from the mayor of Hann-Münden that these papers were still valid, whereupon after much scrutiny, the Commandant wrote and stamped some papers to say that our family was to be excluded from the forced repatriation program, which had been devised by Stalin and agreed to by Roosevelt and Churchill.

“Yet soldiers came for us three times. The first time they came, my father showed them the British Commandant’s note that we were exempt from repatriation. The British soldiers actually saluted my father and apologised for coming that first time. The Russian woman soldier swore under her breath as they left. My parents could hear the crying and screaming of those taken from nearby houses. They could see the truck on the street below and how the British soldiers were beating people to get on the truck. One man slit his throat.

“The second time they came for us, we were in the nearby forest as it was mushroom season. We kept gathering more and more mushrooms and it was dark when we got home. The landlady told us the soldiers had been again and we were lucky we had not been at home.

“The third time they came for us, we were all at home. It must have been a Saturday. As the truck pulled up, the landlady, Frau Töpfer, was just coming out of the house. As the soldier came to the gate, she told them in a cross tone, that we had already been taken and they were wasting their time. She also said she was glad we were gone as she did not want such scum in her building. By some miracle, the soldiers believed her and didn’t bother to go up the two flights of stairs. After they left, Mrs. Töpfer came up to the attic to apologize for what she had said. My parents knew it was just a ruse to make her sound more convincing, as my mother and she were very good friends.

“I was not aware of our precarious life in Germany as I was so young. I only found this out much later when I was about 30, when my father handed me a book called The Last Secret: Forcible Repatriation to Russia 1944-7 by Nicholas Bethell. At the front of the book he had written an inscription saying I should read that book as “this was what had happened to his people.”

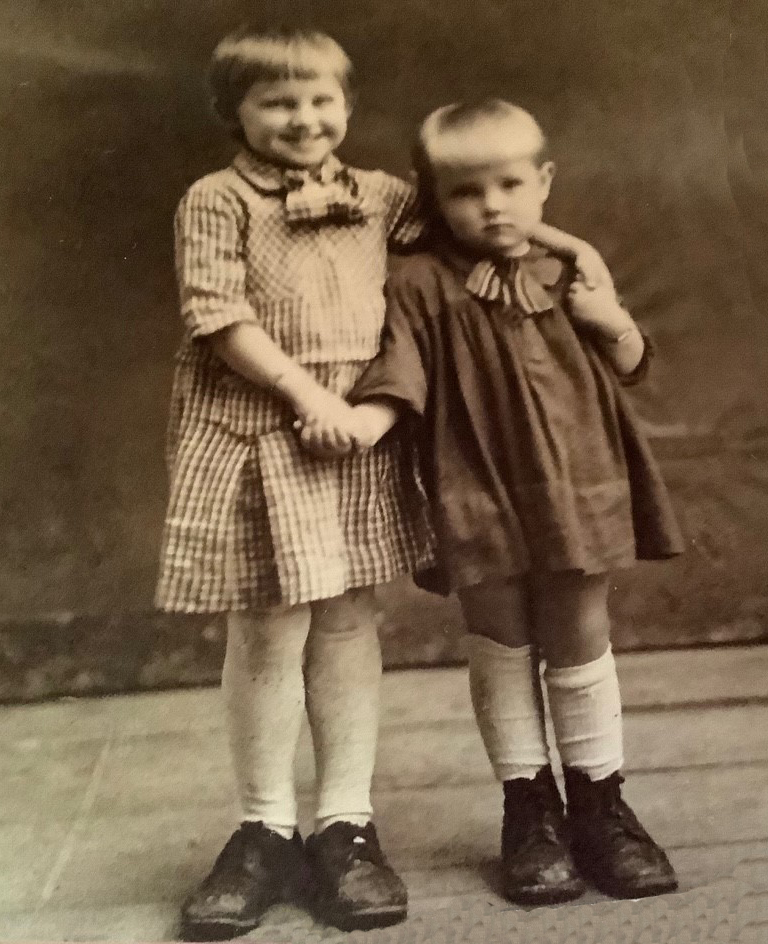

“I have an older sister, Olga, a brother, Alex and a younger sister, Gisela. All four of us won scholarships for tertiary study.

Olga and Erika

“It was only then that I realised “his people” were the Don Cossacks. He had never mentioned that fact to me before. I always thought he was Russian. Now I know that Cossacks are a distinct ethno-social people. Although they lived in Russia they had their own legal and social status and lived in their own territories. Their only Russian government duty was to protect the Tsar and Russia’s southern borders.

“After the end of the First World War and the fall of the Tsar, they had fought to establish their own nation but were defeated by the communists. As a result, they suffered greatly under Stalin and were almost wiped out. Their way of life had been destroyed, their farms and land had been taken from them, they had suffered famines and they were not allowed to practise their Russian Orthodox religion which was extremely important to them.

“On reflection, I should have guessed earlier. I was about 15 when the famous Don Cossack choir came to Sydney. My father had never gone anywhere for entertainment so I was most surprised when he asked me to come with him to their concert. I didn’t think about any possible connection to Cossacks at that time. It was the most beautiful singing I had ever heard. I’ve always loved music. Music, nature and literature are my greatest passions in life.

“Not long after that, the repatriations did stop, officially. However, we were very close to the Russian border and there were kidnappings. People were still being taken and shot once they were across the border. If you were young and healthy, you were sent to Siberia to work in the Gulags.

“As my parents were still terrified that Russian secret agents were after us, they applied to emigrate from Germany to the USA, Canada, Argentina, Brazil and Australia. You had to have a sponsor to immigrate to the USA, which was our first choice. We did not have one. To immigrate to Canada you had to have only two children at most. There were four of us siblings. Argentina and Australia were happy to accept us. My parents chose Australia because of its English democratic laws.

“As I was coming home from school one day, I saw my mother leaning out of the attic window waving some papers and heard her calling out: “Erika, Erika, we’re going to Australia.” I could not believe my eyes nor ears. Why was she screaming out so joyously? What did this mean? I did not want to leave my friends, my teacher, my school. I did not want to leave my beautiful little town, the river that I swam in, nor the forest that provided us with blueberries, wild strawberries, beech nuts and mushrooms. My heart sank. Shock and denial sank into my heart and a great feeling of dislocation swept over me. I became a sad, disoriented little eight-year-old girl.

“My teacher noticed my distress and tried to comfort me. “Think of the wonderful adventure you will have sailing over the sea. You will see many different, beautiful birds and flowers. You will have a better life.”

“The letter granting us provisional permission was contingent on whether all of us would pass stringent medical tests and an interview by an Australian official. As I had been previously sent to a convalescent centre because of ill health and malnourishment, my parents were worried that we would not pass those tests. Luckily, we did.

“Then came the interview. Germans were not accepted for emigration at that time so when the Australian official unexpectedly asked me to say something in Russian, I was shocked. I did not know whether I should say something in Russian as my father had previously forbidden me to speak that language. Neither of my parents told me what to do. The official pointed to the flowers on his desk, then to the table, chairs and window and impatiently asked me for those words in Russian.

“I delved deep into my memory and was able to name those objects in the language I had not spoken for a long time. My parents breathed deep sighs of relief. We had passed the official’s test, which proved we were refugees from Russia and had not previously been Nazis.

“We left Germany in autumn 1949 and arrived in Australia in November, 1949. Our ship was the “General Stuart Heintzelman”. It was specially fitted out to take migrants but it had been a war ship before that. Once we were on the ship, the food was very nice and there was a black cook who spoiled us children, giving us extra titbits and coffee which we’d never tasted before but we liked the coffee even as children. I loved standing on the deck of the ship, looking at the shimmering water, the flying fish and the sun on the horizon. I’d never seen this wide expanse of water before and it was just wonderful.

“We arrived in Sydney on 15th November 1949 in the late afternoon. After we came off the ship, we were herded into a very large reception hall where DDT powder was sprinkled all over us. I still cannot believe that they used DDT even on us children. It was my first horrible experience in Australia. Apparently they were worried about lice. November is cold in Europe and we were all in thick, heavy clothes.

“November in Sydney is very hot. There were long trestle tables with piles of thin cotton dresses in another hall into which we were herded. One of the ladies looked at my eyes when it was my turn in the queue and said: “Oh, you’ve got green eyes” and I was given a green dress.

“What a let-down as I’ve always loved the colour blue and I always thought I had blue eyes. I was so disappointed to get the green dress. After that, we were taken on a bus to Central Railway Station and put on a train to Bathurst. It was quite a long trip and it was getting dark. As I got off the train and stepped down onto the platform everything started spinning around and I thought it’s really true what my teacher told me. The world does really spin around. I can feel it. Then I collapsed and woke up in a ward in Bathurst Hospital.

“They did not know what was wrong with me but they ruled out polio although there were lots of cases of polio during that time in the camps. After a few weeks, after going through a whole lot of examinations, and paperwork and when I had recovered, we were sent to Parkes migrant camp as Bathurst was just a reception centre. We had to stay there until we had suitable accommodation to go to.

“I didn’t see my father very often, perhaps only every three or four months. One incident stands out very clearly in my memory. When he came on one of his rare visits, he stood in front of us children holding out his bare hands, almost crying and said:

“I’ve got nothing to give you.”

We didn’t want anything. We just wanted him to be there.

“All the men that Australia accepted at that time had to be labourers. Educated men with professional qualifications were not accepted. Many migrants were actually professional people but they used to try and make their hands rough so they could show the selection officers that they’d worked with their hands. The men had to agree to work two years as labourers wherever they were sent. They weren’t told that they could be sent miles away from where their families were located. They could even be sent to different states.

“My father was highly educated and had obtained his qualifications as a lecturer in agricultural machinery, cars and tractors in 1936 from the Kharkov Institute for the Mechanisation of Agriculture in Ukraine. He had done extremely well in the thirteen subjects in that course, so was appointed, not as a lecturer but as Head of one of those agricultural institutes. Those qualifications were useless in Australia. The only work he could get was either working in a car factory or repairing cars.

“In our case, my father was sent to Villawood to the Monier Brick and Tile factory three hundred and fifty kilometres away from Parkes. That meant he could not see us very often. The only thing we had ever had was our unity as a family. That’s all we had. We had no possessions, nothing but our unity as a family. We were shocked to be separated by such a distance. That was the cruellest thing of all that we endured in our new life in Australia. Everyone in the camp was shocked to be told – you’re going to the Snowy Mountains, or you’re going to such and such a factory in another state. A father could be sent to one state, the mother to another, and the older kids could be sent to other states. It didn’t matter to the authorities. You had to go.

“If you refused to go to whatever job you were given, the people at the camp would say:

“Right, you can go back to where you came from. You can go back to Europe if you’re not going to do what we tell you to do.” Of course, they didn’t want to lose the migrant workers that they’d brought out here. It was an empty threat as they were too valuable as cheap labourers. However, the migrants did not know that.

“All the mothers and the wives were missing their husbands or older sons and daughters who were working far away. Wives cried for their husbands, children cried for their fathers. We ended up staying in Parkes for two years in Nissan huts that were very cold in winter and extremely hot in summer surrounded by barbed wire and desert. What had we come to?

“One day, wonderful news arrived. My father had bought a block of land in Bass Hill, not far from his work at Villawood. It cost £75 instead of £100. Some months later, he came to fetch us and we were together again at last as a family. It was a most wonderful day.

“The block of land in Bass Hill was totally surrounded by bush. My mother and we children could not understand why he had bought that land in this massively isolated area of Bass Hill. We found out it was because it had been zoned green belt so it was cheaper. However the risk was that at any time the local council could take over that land for public works, parks or whatever.

“Today our parcel of land is part of a lovely golf course. If he’d bought a block of land on Rose Street, we would have had a tarmac road, no bush, and bus and other services. We had nothing. We lived on this isolated block of bush, totally surrounded by more bush, on a dirt road with no houses or neighbours nearby. No electricity nor water was connected to the property. The dunny was a little shed at the end of the block. What a shock that was. I had only known a proper flushing toilet in the house in Germany.

“Our so-called ‘house’ was built from the plans of a small car garage. Only one end of it was covered in and had a roof. The main part consisted of the framework and floor but no roof. My first night in our new home was spent gazing up at the stars and hoping it would not rain. My father would work on it every evening after work and on weekends, until it resembled a tiny house, with an entrance, a small kitchen and one larger room, which served as our living, dining and sleeping room. Our trunk served as our dining table and also as my desk for schoolwork. Five of us lived in that small dwelling until our proper house was completed. My sister had been given a boarding place at a Catholic school attached to the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Parkes.

“One Saturday morning, two nuns drove to our house. When they saw how we lived, they offered me a place at that same school, which I accepted. I had an unfortunate bullying experience there as my English was inadequate. I also did not like the constant prayers held morning, noon and night. I felt I wasn’t learning anything important. I clearly remember thinking, when are we going to learn anything? Our class teacher was a very old nun. There were no maths lessons, only painting, needlework and some reading. When I came home at the end of the term, I begged my mother to let me return to the public school at Chester Hill and she agreed.

“After some time, my father had saved enough money to buy materials to build our proper house. He carefully calculated how much wood he would need for the frame and floorboards and the number of fibro sheets he would need. Then he built a machine to cut the wood and fibro sheets to size. We did not know then that fibro cement sheets were lethal to your lungs when cut, as they then released asbestos. There was no warning on those sheets. My brother and I would be clambering up on the framework to pass him nails and sheets of fibro. He did hire a roofer, plumber and an electrician. It had been a hard year but finally the house was finished. Five of us lived in that two-bedroom fibro house, apart from the school holidays when my sister returned home. Then we were our whole family of six again.

“When I returned to Chester Hill Public School, I should have been put in fourth class but I was put in third class because of my poor English. Our teacher was a very elderly man, who made it obvious he did not like children nor teaching. He used the cane frequently and almost sadistically with regard to one boy who was always misbehaving. I was a good, quiet student, eager to please but felt upset at the constant caning.

“One day a boy from another class came to tell him that the headmaster wanted to see him. Before he left the class, the teacher wrote the names of vitamins on the blackboard and told us to behave while he was gone and to copy those vitamins in our books. As soon as he left, the boys leapt out of their seats and created bedlam. The other girls and I studiously kept on copying down those vitamins. When that teacher returned after about a quarter of an hour, he looked very angry. Obviously the interview with the headmaster had not gone well.

“When the boys heard him coming back they had leapt back to their seats and pretended to have been well behaved. Our teacher must have heard the uproar from a distance. Angrily he pointed to some of the boys and girls, including me and some other migrant students, and told us to come and stand in front of the blackboard. We did not know what was happening, until he rushed to a cupboard, pulled out a cane and screamed at us to hold our hands out. We were so obedient, we did. With a mad look in his eyes and spittle on his lips, he lunged at us with his cane. The cane stung my hand. I felt distraught and ashamed. I am still angry at that injustice.

“To be caned made me feel worthless and so ashamed. I could not tell my parents and worry them with my pain and my feelings of unjust and irrational abuse. What could they have done? We were the despised ‘New Australians’ who could not even talk in English and brought strange food to school. The next year, that teacher had left our school and was replaced by a kind and more proficient teacher, a Welshman. I thrived under his tutelage and regained my confidence. In third class, I could not speak English. In fourth, fifth and sixth class I was top of the class and was supposed to go to a selective school, Parramatta Girls High.

“However the Wyndham Scheme had been approved. Comprehensive schools had become the vogue and had started to be built in the rapidly growing migrant areas in the western suburbs of Sydney such as Cabramatta, Fairfield and Liverpool. Liverpool Girls High had just been completed, so that was where I had to go. Our teachers were young and inexperienced compared to the teachers I would have had at Parramatta, who had years of experience preparing students for the Leaving Certificate, which is now called the HSC. Nevertheless, a number of us did well and won scholarships to Sydney University. The founding Headmistress was Miss Campbell and she was so proud of us that she invited us for afternoon tea to her lovely unit in Elizabeth Street in Sydney.

“I wanted to teach German and English, so these became my majors, which I studied for three years. My other subjects were Psychology and Anthropology. After the degree, I studied for a Diploma in Education. I liked being at Sydney University but it was difficult to get there from Bass Hill. It was a long trip. It wasn’t so difficult in the morning because the public transport was reasonable then but if you had to stay back in the Library as you often did, the transport back late at night was just hopeless. There used to be buses to our place from Yagoona station but they’d stop at a certain time and then I’d have to get a taxi and I couldn’t really afford that. I didn’t have a social life at all. It was just a life of going to lectures and going to Manning House for a cup of coffee with my Ukrainian girlfriend, Halyna. My time was so constricted because I worked every weekend as a wards-maid at Lewisham Hospital.

“My first appointment was to Maroubra Bay High. My whole timetable consisted of teaching German, which I loved. The students were very bright and eager to do well. A television series was made about Maroubra Bay High. It was called ‘Heartbreak High’ and was sold all over the world. Now that school has been taken over by a housing development. By the end of the year, I was getting itchy feet. I wanted to return to Hann-Münden, the place I had so reluctantly left and which had stayed in my heart all those years. I repaid my scholarship money and booked my fare.

“The ship was the P&O liner, the “Canberra” and young Australians were going to England to their “Mother Country”. I was in a cabin for four and made friends with the other three girls. It was a lovely trip. The food was delicious and there were dances and other entertainment. Towards the end of the journey my cabin mates asked if I would you like to share accommodation with them at Earl’s Court and I leapt at the chance of sharing with them. My first job in England was a short-term appointment teaching English at a Salvation Army girls’ home. It was a home for underage “wayward girls.” I felt sorry for them because all they had done was to have affairs with their boyfriends. They were in a “home” whereas their boyfriends were free to do what they liked. It seemed unfair. I then got a job in the Houses of Parliament. My job was to summarise speeches and papers written by members of parliament for publication in “The Commonwealth Parliamentarian.”

“When my flatmates had dispersed to other parts of England, it was time for me to take the plunge and return to Hann-Münden. I was overcome with emotion when I was allowed to go up to the attic and found that refugees from East Germany lived in that attic now. When I saw mattresses on the floor, I burst into tears. The fact that such poverty as we had experienced continued to that day undid me. My fear of poverty still haunts me.

“However, none of the former residents were still there. I then walked through the town, the square with the wonderfully painted front door of the town hall, dating back so many centuries, looked at my school, which had been decommissioned and replaced with a brand new school, visited the former castle which is now a museum, and walked down to the river. The embankment is now a vista of summer houses and bountiful gardens, brimming with fruit and vegetables. My broken heart caused by my unwilling departure from Hann-Münden was now whole again. I felt spiritually restored.

“By the time I returned to England, my Australian qualifications had been verified so I started teaching again. I started to take week-end bus trips to discover more of that verdant countryside. On one of those trips, I met my husband, Keith Bernarr Redgrove. We started chatting. When I said I’d just come back from Hann-Münden he asked why I had gone there. I then told him my story. We got on very well and exchanged contact numbers. After some time, we started dating. We had a lovely garden wedding at his parents’ heritage listed house in Kent, when we married on 22nd October 1966. In April 1967, I returned to Australia to introduce my husband to my family.

Back row: John Stevens, Garry Ellis, Ross Matheson, Lex Crosby, Stephen Riley, Warwick Hadfield, Robert Kearney, Les Stathi, Rodney Weise,

Second row: Christopher (Kim) McRae, Phillip Avery, Bill Purdie, Bernie Hawke, Mark Hungerford, Graeme Wells, Bruce Hamilton, Richard Parkes, Michael Lesevic,

Third row: Larry Lazarides, Slowka Wenc, Sue Piechowski (now Suzanne Mulligan), Lynne Shepherd, Olga Tchadovitch, Barbara Kelman, Stanley Fienberg, Mrs Redgrove,

Front row: Fay Nichols, Kristine Newton, Jan Buttsworth, Linda Button, Margaret Rozeleur, Sandra Hulbert, Judy Dillion

“My first teaching appointment on my return was to Richmond High School, in the Hawkesbury district of NSW. My whole timetable was teaching English so my classes ranged across all abilities which I enjoyed. You need to find different methods to teach different interests and abilities. I enjoyed the challenge of making my lessons interesting. The students were wonderful, well-behaved country kids. It was a real pleasure to teach them as they were eager to learn. Quite a number of them achieved illustrious careers and I have been lucky enough that a number of them have kept in touch with me.

“Four years later, I was expecting my first child. There were no childcare facilities in the Hawkesbury at that time. I had to find a babysitter. I continued teaching at Richmond High but two years later I was pregnant again. At that time, you were only entitled to six weeks’ maternity leave. If you wanted longer leave, there was no alternative but to resign.

“I cared for my sons until they were ready to start kindergarten. However, as luck would have it, the 1970s and the 1980s were not good years to seek re-employment. Australia fell into a deep recession, heads of schools were ordered to cut back costs. No full-time, permanent positions were available in the Hawkesbury. I could teach as much as I wanted as a casual but that was disheartening. Students knew you were there for just the day. It was hard to establish rapport and they were not interested in learning from a ‘casual’ teacher. I needed job satisfaction. Furthermore, the Education Department could offer me a job which would require travelling a long distance from home. That would be difficult with my two small children, who would need to be picked up after school. I realised I would need to retrain and find a job with more autonomy.

“I decided to enrol in a Graduate Diploma in Library Science at Kuringai College of Advanced Education, now part of UTS. At the end of the course, Professor Joe Hallein and I worked together on a research project on school, college and public library co-operation in the Windsor/Colo district. Later, its recommendations were successfully implemented and the report was published. I had interviewed the Head librarian at Hawkesbury College of Advanced Education in Richmond, so when the college advertised for a cataloguer, I applied and was successful.

“At Hawkesbury I progressed from that position to Reference librarian, Head of Client Services and Manager of Education and Research. That last position enabled me more interaction with staff and students. I held classes in copyright laws, academic referencing and online information retrieval offered by Dialog Information Services. When the college established its first Learning Development Centre, I was appointed as its first Head. As an elected member of the Academic Board, I contributed to its work for the establishment of a university for western Sydney. Equity issues were very important to me. I became the College’s first Ethnic Affairs Co-ordinator and was on the E.E.O. Committee as well as Appointment Committees. My time at Hawkesbury C.A.E. was interesting, challenging and satisfying and I am grateful for the opportunities given to me.

“In 1995, I attended a conference in Hobart. It was the first time that I had visited Tasmania. I had added a week’s leave to the end of the conference so that I could go on a short tour. I was awestruck by its topography and persuaded my husband to visit the state. He too enjoyed the scenery and thought we should buy a holiday house. After I had retired, we moved there permanently. Our younger son came with us, as he had won a scholarship to study for a PhD at the University of Tasmania.

“My wonderful husband and I enjoyed almost fourteen years together in Tasmania before he died in September 2014. I miss him terribly. I also miss my elder son and my grandson and relatives in Sydney. When I can, I go over to see them and my friends in NSW. I have good friends and relatives in other states and overseas. I enjoy travelling in Europe and have made quite a few trips, not only to Germany but also to France, Italy and Spain. Our trip in 2017 was exceptional as my son and I had been invited to stay with a German aristocrat whom I had met in Tasmania and we had ended up staying overnight in his centuries-old castle!

“I am so very lucky that former school students, particularly those from Richmond High, still keep in touch with me. Warwick Hadfield OAM, an ABC sports broadcaster is one of those students and was kind enough to welcome me to Tasmania, when we first moved here. I am especially grateful to another one of my former students, Sue Mulligan, for introducing me to a new interest – that of oral history and for her work for me in that regard.

“When my family and I came to this country after the Second World War, Australia was close to ninety-nine per cent of Anglo-Saxon stock and people were not used to diversity. At first we were ‘New Australians,’ rather nice words, but soon became ‘Reffos’, ‘Balts’ and with the arrival of Italians, ‘Wogs’. It took thirty years of seismic historical and social changes, before Australia began to develop into one of the most successful multicultural nations in the world. I have written my memoir which recounts not only my personal experiences of migration and of becoming an Australian but also those of other migrants in the context of those momentous changes. Whether my memoir attracts a publisher is yet to be seen.”

Erika Redgrove was interviewed in October 2022.

She was my English teacher when I attended Richmond High School, New South Wales.