John Preece was born in Sydney, Australia in 1945. At the time of the first moon landing in July 1969 he was working at the Carnarvon Tracking Station, West Australia. This is his story:

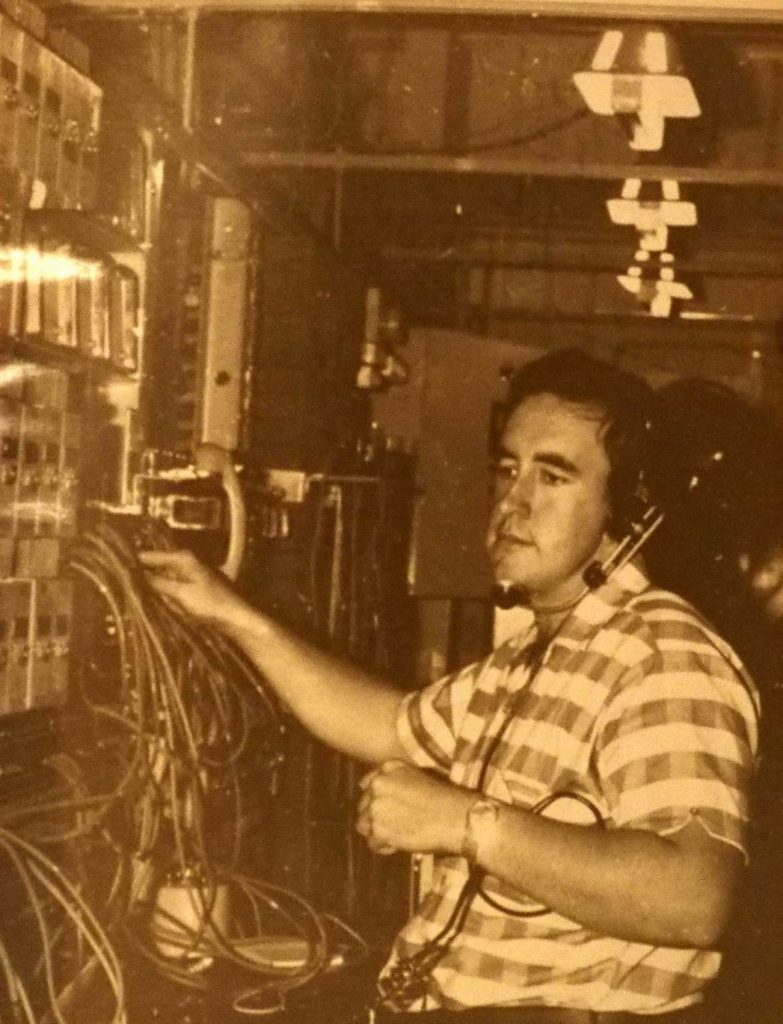

“I grew up in Sydney, spent my whole life in Sydney till I was about 22. Then I did an apprenticeship in telecommunications in Sydney in the mid-60s and the company I was working for then was Plessey Communications, a fairly big British company. When I completed my apprenticeship, rather than be moved on to another company, they offered me a permanent position, of a tradesman. I was there for about 12 months and then they offered me a tradesman’s position with their branch in Perth, which I took up. I was there for some time, the timings get a bit hazy, at least 12 months. Then I saw an ad in the paper for a telephone technician, they required at the NASA Tracking Station at Carnarvon. I applied for the position and much to my surprise, I got it and I was there for two years, from June 1968 till June ’70.

“When I first went to Carnarvon, the furthest north I’d ever been out of Perth was Geraldton, which is about 300 miles and Carnarvon was 600 miles. No internet then of course. I looked at the map and north of Geraldton, about 60 odd miles was Northampton and then there were two quaint dots on the map, the Overlander and Hamlin Pool. I thought, nice names for towns. When I drove through there going to Carnarvon they were on the main road. They were both roadhouses. It was bit of a bit of a culture shock. When you arrive in Carnarvon, the north-west coastal highway was the main coastal road going to the north of the state. You could virtually follow it right through to Darwin. You come to a T-intersection. You make a right turn to go east or to go north or a left turn to go into town. When I arrived there, obviously I had to turn left. Looking at the sign going east and north, there was a big Main Roads Dept sign naming all the main roads in the area and each road had a triangular rotating sign attached to it. So depending on the road conditions, they could change the sign and close the road due to the weather because there was a lot of dirt roads up there. Later on, you would see them change to 4-wheel drives only or semi-trailers. At that time if they were caught driving on a closed road, they were fined as per axle. And of course, in those days, you had the prime mover which was three axles, and then you may have had one two or three trailers behind it. So it didn’t motivate you to take a short cut.

“The population of Carnarvon back then was less than two thousand people. Carnarvon then was a pastoral support and fishing town. A few years earlier, a whaling station there had been closed down as they all did in Australia in the early ’60s. If you had a family, you were provided a house in town. If you were a single person, like I was at the time, there was single person accommodation at the rear of the Port Hotel which was one of the premier hotels in town at the time. The owner licensee was the Wilson Tuckey (Federal MP 1980-2010). When you arrived there, you went in, paid at the desk and, “Oh yeh, John, no problems. Your unit’s out the back.” They were blocks of units and you’d share an ensuite with the person next door, which was never a drama. “And that hasn’t been vacated, no problems. We’ve allocated a room for you in the hotel proper.” And at that time, part of the deal was you’d have all your meals in the hotel. So being in a room upstairs wasn’t an issue but the room that was always allocated in the first instance was directly above an aboriginal bar, which in those days was very common in the nor-west. “And, ah yeh, that’ll be okay.” And problem was because you’re above the aboriginal bar, they played the same Slim Dusty record over and over and over. One morning, one Sunday morning, before the bar had been open, they were actually cleaning out that bar so I snuck in and had a look, and guess what! They had more than one Slim Dusty and other records in the machine, but they just wanted to play this one over and over. And then I got moved into end of the single units down the back.

“When I started work at Carnarvon I was only 23 years old and I didn’t realise how leading edge this whole thing was at the time. My first day at work was a bit like, gee whiz because I hadn’t seen this technology that had never been seen anywhere in Australia before. One of the big surprises – first time I’d seen bubble wrap. Everything that come from the States that was sensitive was in bubble-wrap. They also provided a limited tool kit and it was the first time that I’d ever seen split bladed screwdriver. On the shaft, it had a sleeve but at the end it was split and as you pushed the sleeve down the shaft, it would thicken the split up so you could actually hold the screw at the end of the shaft and put it vertical or in an awkward place with one hand, just get it started and then use a conventional screwdriver to finish off. They were some of the new things. One of the things that struck me when I arrived there – I think it was Apollo 9 or Apollo 10, due to equipment, the lunar module and the command module were built by separate companies. The lunar module wasn’t ready for the Apollo 8, one of the earlier flights. Everyone had this esprit de corps around the place and, you know, all gung ho.

“My supervising engineer was Max Beresford and then I worked with John Harmson and Ian Squires. They were the main two people I remember working with. The supervisor was Paul Linanne. He was my supervisor and there are stories that go on at the tracking station you can’t talk about. I wasn’t there for the construction of the tracking station but, now they tell various stories and in the main building, because of all the cabling, it’s standard today with computer floors, the floor was raised about two feet and you had these about two foot square vinyl tiles on frames and you had suction caps to lift them up. You’d have cables running everywhere and when they’d be identifying cables, there’d be one bloke had the cable at one end when it was going to come out in to the work area and be on the edge of the building that were then, because the cables were all grey. Anyhow this particular day apparently they were identifying cables and give the cable a pull, yep, yep, yep, that’s the one and this bloke was under the floor giving the cable a pull, yep, that’s the one and okay last one, you didn’t get a yes, you got an almighty yell. He was pulling a snake. He come out of there like a rocket. Within 24 hours all the open cable entries to the building had been sandbagged. But, you know, that was what it was back then.

“There was over 200 people working at Carnarvon at its peak, which was more than the total of the rest of the tracking stations throughout Australia. It was in a primary position because the tracking station at Carnarvon was 180deg around the globe from Cape Canaveral. So after they were launched, it was in the optimum position for tracking because they used to do at least one or two orbits of the earth. Then going through Carnarvon, if everything was okay, they’d be given the go ahead from Houston to fire the last stage of the Saturn V rocket booster, to head for the moon. When these spacecraft are in Earth orbit, your tracking is only for one to two or three minutes, depending on horizon to horizon.

“First of all, we have some idea where we’d expect the spacecraft to appear on the horizon. There were sub-groups of equipment doing various roles and they’d be all pointing in that general direction. And one of the sub-groups was, Acquisition Aid (ACAID), which was a very sensitive piece of equipment. They’d be positioned where they really expected it to come but if it was a bit off, they could still pick it up. All the other sub-systems would be linked to ACAID. When ACAID had had the signal, he would call internally, ACAID AOS which is acquisition of signal. The other sub-groups, if they had already got it, would lock on to his position and they would call RF command, AOS USB AOS every EPQ6 radar AOS, range rate, AOS when they have all called in, the Ops Controller in the Control Room at Carnarvon, he would then go out on the network “Houston Carnarvon AOS”, and then that was the cue for Houston to call the spacecraft and when they did, it would be, depending on what the spacecraft was but on the manned missions, Apollo 11 all the time, “Apollo 11 Houston through Carnarvon”. Then on the Apollo 11 mission, they pass on some general technical information and then after they’ve done that, there’d be a little bit of a pause and then Houston would be “Apollo 11 Houston through Carnarvon you are go for TLI”. TLI was Trans Lunar Insertion and that was their approval or permission to fire the last stage of the Saturn V booster and go for the moon.

“If there’d been a problem with the tracking or something else they would, instead of saying go, would be a no-go, and then they would continue to orbit the earth till they sorted the problem. If they couldn’t, then the whole thing would change inasmuch as getting back on the ground. It never happened. Every Apollo mission, they were all successful. And it’s to be noted that on all the launched Apollo missions they never lost anyone in space, except during a training simulation.

“Very early on, they lost three astronauts on the launch pad (Apollo 1) because with that particular simulation, it would start maybe two or three days out, following the normal script and on the tracking station you’d be doing your normal functions as if it was a real mission you were counting down for. Then the astronauts actually went into the spacecraft on the launch pad and they closed the hatch door. In those days they bolted the hatch door shut. Then there was a fire inside the capsule. The capsule in those days had a 100% oxygen environment and the fire was ferocious and they could not get the astronauts out because they couldn’t unbolt the door in time. Subsequently, they then developed explosive bolts so in an emergency, they could blow the heads off the bolts and get them out and that was the only tragedy they had in the Apollo series. But it delayed the whole program by 18 months till they worked out what went wrong, why it went wrong, and how do we to get it right. Indirectly, that gave me the position in Carnarvon because if that delay hadn’t happened, they probably wouldn’t have advertised the position when they did. Also at the time, though Carnarvon wasn’t hands-on tracking, you could hear the traffic in the network and then all of a sudden you heard one of the astronauts call “Fire, fire in the capsule”. Initially, they thought it was part of the simulation, like they’d throw a problem in and you’d have to deal with it. Initially they thought it was part of simulation and looking for the procedure to deal with it and then it became very obvious it was a real fire.

“I mentioned earlier about how all these people are gung ho. Apollo 9, Apollo 7 and Apollo 10 were all earth orbit, training with various things. Every time Houston would call the spacecraft and they’d snap back straight away with a response “No problem” and then when this particular spacecraft splashed down Houston is calling them because, prior to that, when the spacecraft returns and the heat shield was basically a shield around the spacecraft and they have a radio blackout. So, until they actually hit the water, or could be a bit earlier, they don’t have communications and you wait for them to give a call. So they splash down and then Houston is calling them because there’s helicopters in the air and they have divers ready to jump into the water from the helicopter to put a floating collar around the spacecraft. So Houston’s calling it, and no response, calling in again, no response. At that time we had the Apollo ranging and instrumentation aircraft which was a modified military 707 which had a big tracking dome in the nose. It was calling the spacecraft through ARIA (Apollo Ranging & Instrumentation Aircraft), no response and also through the aircraft carrier that was supporting the recovery, no response, and then suddenly the spacecraft responds and I suddenly realised I’d been bitten by the bug because I started breathing again. I didn’t realise I’d stopped breathing. Yeh, and then there was, you know, progressively moved on.

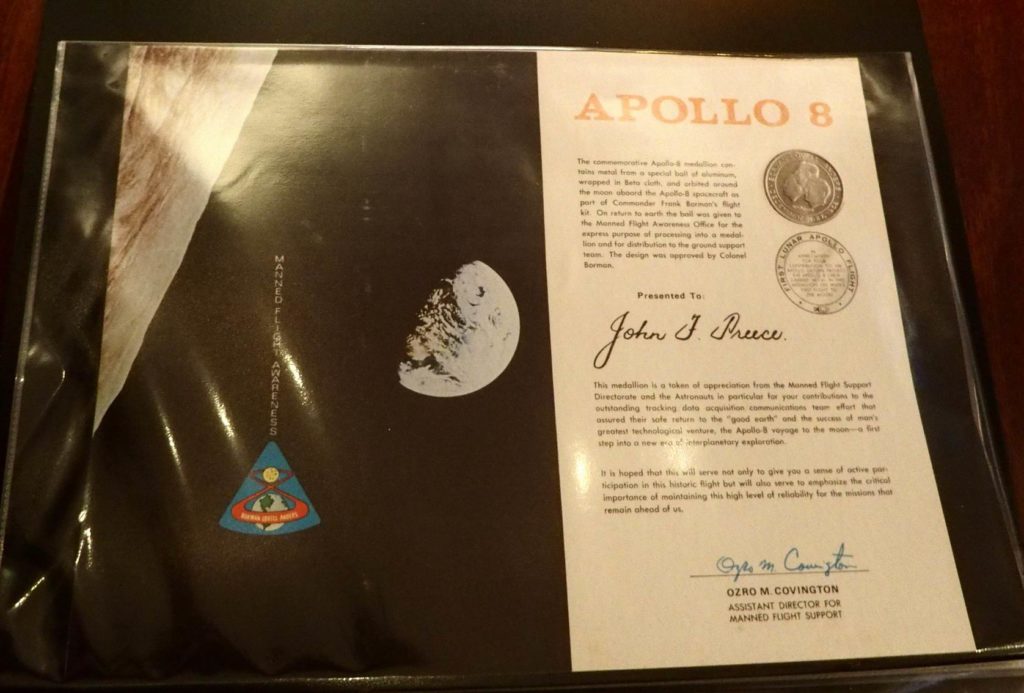

“The other big one was Christmas 1968, the Apollo 8 mission. The Lunar module wasn’t ready so they still elected for Apollo 8 to loop around the moon and when they looped around the moon, the other thing with that was that once they go behind the moon, and they do a burn to slow them down or they do a burn to turn back. Houston then tells them beforehand, you’ll be AOS, at such a time with a burn or without a burn. So everybody gets the silence because they’re behind the moon and then you’re waiting.

From the moment they’re launched, Earth time, for want of a better word, 24-hour time doesn’t exist anymore. The Earth time is Greenwich Mean Time and they use what’s called – Ground Elapsed Time. That starts from the point they’re launched. And everything happens on certain Ground Elapsed Time. On the tracking station they’ve got two large digital clocks, one above the other. One displays GMT, the other displays GET. And about 15 minutes after launch, an operations person in Houston will call, on my mark, set GET clocks on my mark at 15 minutes x seconds, x 100th of a seconds, give you a couple of seconds to punch it in, MARK. And everybody would set the clocks going and you had a number of these clocks around the station as well and everything would work on that time. So then you’re waiting for them to call up as they come around behind the moon. When they did it Christmas Eve 1968, and I can’t remember now whether they actually orbited the moon or they just did a loop behind the moon. There was never any intention that they were going to land on the moon. Then they did a live TV broadcast, on prime time US of course, which was Christmas Eve and, I think it was Lovell, the Commander, he quoted a piece from Genesis – God made the Earth in seven days etc. and finished with, “Goodnight and God Bless from us to the people on Good Earth” and that blew me away, part of it blew me away but not so much the way they said it, but you’re thinking of these people, that are very serious gung ho engineers. You know, you didn’t expect that from them and something that I’ve never never forgotten.

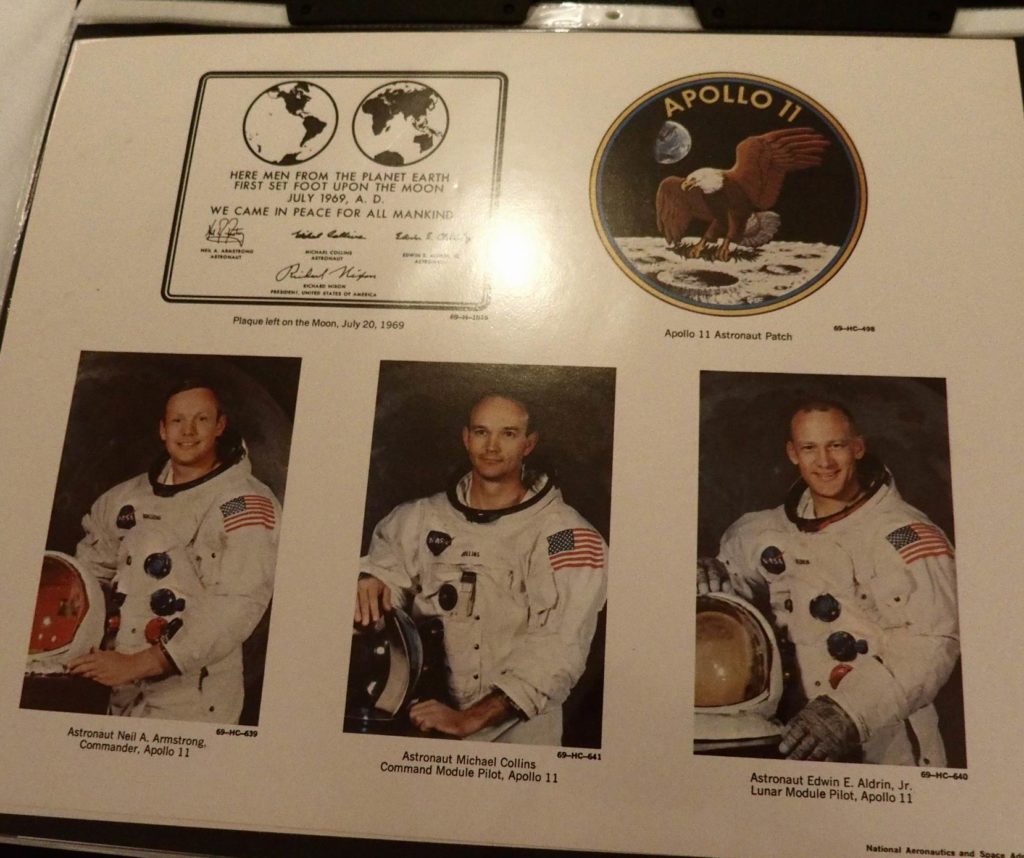

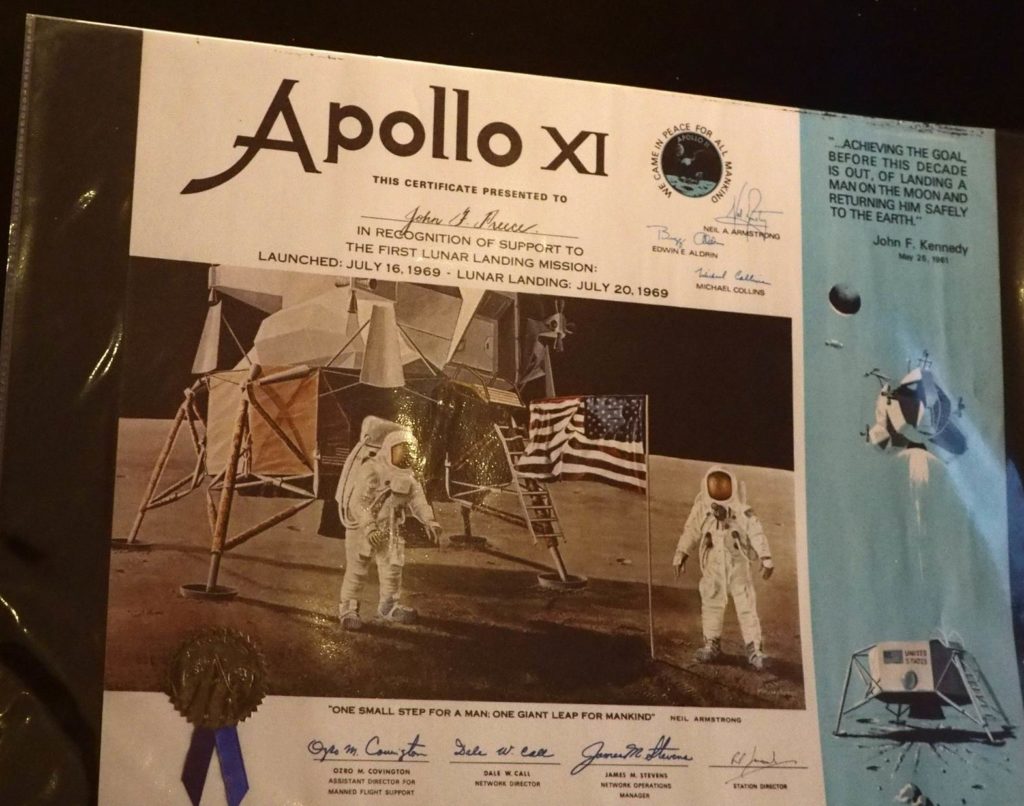

“Then of course, there was the Apollo 11 mission that went like clockwork. People didn’t realise then and I don’t think they realise now, those astronauts knew that they had a less than 50% chance of actually completing the mission.

“They were launched 16th July, and then 20th July [21st July Australian time] they landed on the moon. Australian/American time there’s a 12 hour difference. In Carnarvon, back then there was no television. You only had ABC radio, which I’ll come back to in a minute. And we weren’t tracking when they actually landed on the moon but we could hear everything that was going on, which wasn’t a problem. And, the ABC, sometimes we get more information listening to ABC radio than what was going on the network. Back in those days at 12 midday there was normally the ABC News followed by the Country Hour. Comes to 12 o’clock and the broadcaster comes on and said, “We will stay with the moon landing and there’ll be no ABC News and no Country Hour.” No problems and understandable. Five past one, “We will leave the ABC Studio there from the Apollo Studio in Sydney for now for today’s episode of “Blue Hills””. And then about 1.25, 1.30 they returned to the Apollo Studio in Sydney. Yeh, yeh, yeh, could not believe it! One of those things that sticks in your mind. And you could imagine the celebration when they did land on the moon and come back safely.

“Apollo 10 launched May 1969 and was deemed a dress rehearsal for the July Apollo 11 moon landing. Subsequent missions, (except Apollo 13 of course) Apollo’s 12, 14, 15, 16, 17 were even higher risks because of what they were doing on the moon in a Rover and moving around away from the spacecraft. Because when they landed on the moon in Apollo 11, the moment they touched down, Armstrong was ready to take off straightaway, just in case something untoward happened. They only moved a short distance away from the lunar module, raising the flag, taking soil samples and setting up a few experiments.

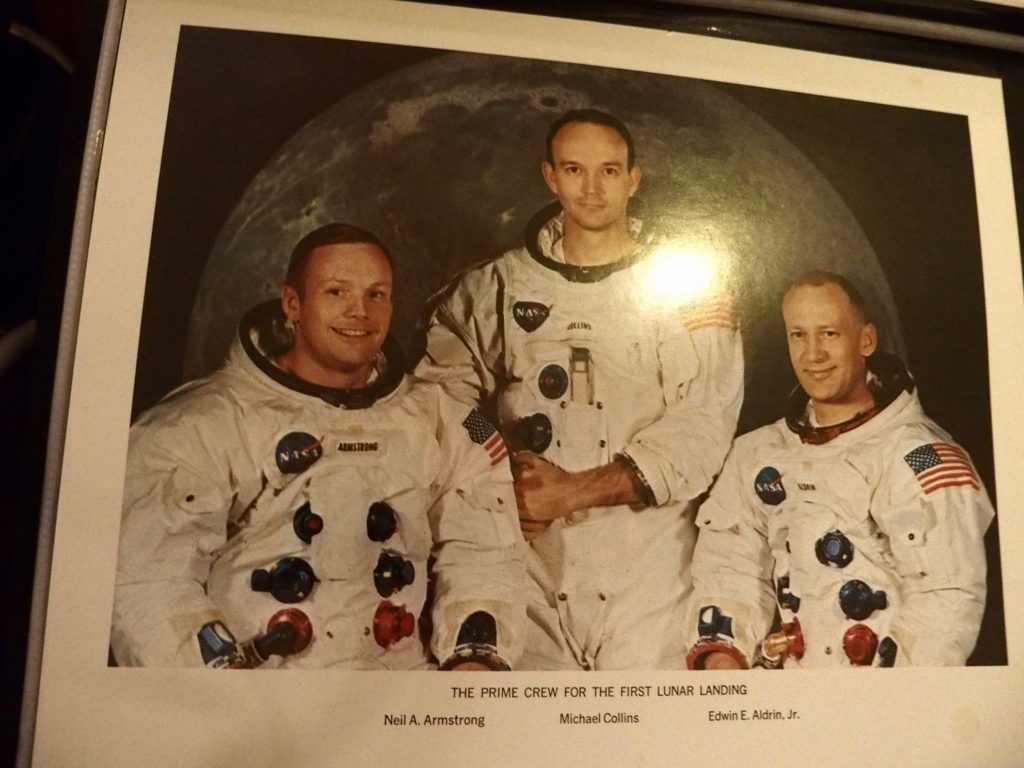

“The astronauts on Apollo 11 were Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Mike Collins. Mike Collins has become known as the “forgotten man” because he stayed in the Command and service module and orbited the moon until they returned to the spacecraft. If you see pictures of the Saturn V rocket, there is what looks like a spike or a needle right at the tip, an orange painted needle. That was the launch escape mechanism. Once they were locked in the capsule, and the gantry had moved away, if anything serious had happened, they could then evacuate by activating that, which was a mini rocket that would lift the command module free of the vehicle and then take them high enough at a splash down in the water. That was the theory. The practicality was, if it was that bad, by the time they did the normal reaction to “we’ve got a problem, we’ve got to get out of here” and then have the rocket generate enough power to take off and move away they believe either they would get caught by the explosion if the vehicle exploded or the pressure blast would have killed them and as one wag said “oh and it also would have caused a great hole in Florida”.

“We were hearing the touch down very very live though the network. We were hearing the real thing. Surprisingly in the last few weeks, NASA or US has actually acknowledged that the clear footage of Armstrong stepping on the moon actually came from the tracking station at Honeysuckle Creek outside of Canberra. The media geniuses at NASA wanted the landing on the moon to be shown in prime American time and the station that was to track it was Goldstone in California. Problem was Goldstone and the moon weren’t in optimum position and even media people couldn’t move it. When they started to take the signal, they were getting these very very fuzzy pictures. Just to backtrack a little, in Australia all the communications and everything were fed back to a control centre above the Deakin telephone exchange in Canberra. They would then feed it to Paddington telephone exchange in Sydney and at Paddington, that’s where they had the undersea overseas cables and everything coming in and they would send it back to the US. So hearing these comments about the picture being grainy, suddenly the controller at Deakin, he goes out on the network and says “we have a clear picture from Honeysuckle.” So that’s the clear picture you saw.

“We could hear it, stunning because there’s a classic, when Armstrong’s actually coming in to land and he’s calling all the time, height and drift and various other things and then suddenly they had a 12.02 or 12.01 alarm and no one knew what it was. They didn’t know what the implication was. And then suddenly you see that huge control room in Houston, each one of those consoles is backed up by a backroom of maybe 15 or 20 engineers and the engineer and then one of these junior engineers put his hand up and said “I’ve seen it in a simulation, the computer’s saying ‘leave me alone, I’m getting too much information’.” Because what Armstrong had done, their landing site was deemed unsafe with boulders so he activated his terrain radar as well and the computer, was saying “leave me alone” and then they made the call to ignore it, continue then a short time later, gets a 12.03 alarm which was basically, “I told you to leave me alone”. And then they were also running out of fuel, because he had to change location when they landed, there was only about 10 seconds of fuel left and when he landed he made the formal call. Instead of Apollo 11 was, “Apollo 11 Houston the Eagle has landed.” Houston’s response was along the lines of “We copy that. There were a bunch of guys in here about to turn blue, they’re breathing again.” “Then a little bit later on you had Nixon come on and give’em the, you know, “well done.” What people of course didn’t know at the time, on Nixon’s desk was also a eulogy to three brave American men.

“When Armstrong landed we were elated about it but because we weren’t tracking, we weren’t actively doing something. See on the voice networks, there were three networks. One of them was Net 1 which was the ground air communication with the spacecraft, other than God only the Capcom, Capsule Communicator, in Houston could talk to the spacecraft unless there was a major failure of Houston and then the Ops controller at the ground station could talk to the spacecraft. Net 2 was to do with tracking and other operational stuff. Net 3 was a sort of a general channel about various things and in my role as American expression of a Wiretech, you’d be listening to all three networks at the same time if somebody called you or you would hear a change in the timbre of the voice or something.

“We heard Armstrong’s words, you know, “One small step for man and one giant leap for mankind”, yeh. Then Buzz Aldrin left the spacecraft and joined him. There was a lot of speculation at the time that there was a fight between Armstrong and Aldrin, who gets out first. But they had no choice. The Lunar Module was so small. The one nearest the door had to get out first because with the space suit on, you had no chance. And another thing that Aldrin said, and he was the Lunar Module Pilot. When he got back into the spacecraft and got ready to launch to rendezvous with the Command Module, the lever on the toggle switch had been broken off. And that was the switch that armed the spacecraft to go into the launch mode. He used a pen as the lever to activate the switch, because there’s no RAC around then. Yeh. You know it was all, all sort of normal.

“Now I worked at Perth airport for 40 years in both Airport Fire Service for 16 years and a Terminal Operations for the rest of my career, left as a Duty Manager. And, as much as I enjoyed my time at the Airport, those two years at Carnarvon was the greatest job I ever had. And it wasn’t until four or five years later, I realised how good Carnarvon was. I get annoyed when people misquote that scene from Apollo 13. People say “Houston we have a problem”. Apollo 13 never said that. Apollo 13 actually said “Apollo 13 Houston, we’ve had a problem.” and Houston’s reply was “Yes, we’ve copied that on the ground. We are looking at it”. So getting it in to context because what I was saying before you’re listening to the network and I was working that day. You have two stations tracking at the same time, a prime and a backup, and suddenly FIDO which is a tracking Manager, goes on the network, tells the backup station to go prime and to change your header to JJ. That’s the way the communications are directed and the prime station to go backup because Houston had suddenly lost this big bank of data and by doing the big swap over, they would then know if it was a ground station or a land link problem back to Houston, or a ground station problem if they were getting good data from the backup side. What did scare them as well, if it had been a ground station problem, they would have called it basically simultaneously when they had it come down. When they found they were getting the same thing, they knew it was coming from the spacecraft and that’s when the spacecraft called up and said they’ve had a problem. They were on their way to the moon. If they’d have been coming back from the moon, they would have all been dead because the three astronauts lost a life support system in the command and service module. They then moved into the lunar module, something designed for two men, not three men. And then, as things progressed, time-wise they were running out of carbon dioxide filters in the lunar module, and so he was – oh, that’s all right, we’ve got filters unused in the command module. Only problem was, like I said earlier, because the two vehicles had been built by two separate companies and size was an issue, the filters in the lunar module were cylinder shaped, the ones in the command module were square. So a group of engineers on the ground assembled in a room. An Engineer brought in a box basically tipped it on the table and said – right, make that go into that. That’s all they’ve got in the spacecraft. And then they sent up a procedure. The astronaut said later, his step one is – take the manual and tear off the front cover. He said “It gave me the greatest pleasure to do that.” and we all know, Apollo 13 returned successfully.

“And then there were four more missions after that. The last mission was Apollo 17. You hear from time to time the conspiracy theory that it never happened. Well, people my age now, if that had been a real conspiracy, at the time, the height of the Cold War, don’t you think Russia and China would have been screaming blue murder, or after 50 years someone would have made a deathbed confession, or even more people sold their story to “60 Minutes”. And recently, prior to Neil Armstrong dying, astronaut Gene Cernan was asked about the conspiracy, and he said – “Yep, they were asked that question and their short response was – you can get away with it once, you can’t get away with it six times.” And as I’ve said – it’s still the greatest job I ever had and things like what they said when they landed on the moon, and what Apollo 8 said from the moon, I remember that as though it happened yesterday.

“A big tragedy about Carnarvon now is there is nothing on the NASA site whatsoever except at the base of the ABC TV tower, there is a brick building and that used to be part of the SPAN, the solar particle alert network. All the time the sun was out, they had a telescope tracking the sun looking for solar flares. If there was an abnormal solar flare, they would take a colour A4 size photograph of it, develop it at SPAN and then they would put it on a machine with a stainless steel drum and then they would fax it back to the United States because the solar flares could impact on the astronauts if they were outside the spacecraft. And just by coincidence, when I arrived in Carnarvon, that was the first job I had was installing cables in the SPAN building on a rack outside but within the building and it had been raining. The ground was very wet. I became very acquainted with midges around the ankles and they sting and you scratch and you get your ankles infected. You become very aware of midges.

“In the 1980s I took my Father to visit the Tidbinbilla Tracking Station. Because of Australia’s involvement in the space program NASA, or the US government gave Australia a piece of moon rock and it was to go on display in the Visitors Centre at the Tidbinbilla Tracking Station outside of Canberra in the ACT. They had a story in the local newspaper here in Perth about it. Dad was terminally ill at the time but I spent some quality time with him. And so I rang the Visitors Centre to find out when it was going to be on display. The receptionist there said – “Oh, look I don’t know. I’ll put you through to somebody that can help you.” And this gentleman answered the phone with the tone of his voice before I’d even said anything was like – why are you bothering me at my morning tea, or something similar. And I said, “A piece appeared in the paper here about the moon rock. When’s it going to be on display?” “What do you wanna know that for?” I said, “Well, Dad and I have come in to Canberra and going to Tidbinbilla, want to sort of coincide the trip. We wouldn’t like to miss it by a day.” and I said, “I also worked at Carnarvon between ’68 and ’70.” You would swear somebody else had put the phone down and someone else had picked it up because it was – Oh, did you know? Yes, yes, worked with him. He was my supervising engineer, know him, he was in another section. Oh don’t do this Visitors Centre crap. He said – it’ll be on display from such and such a date. Ring me the day before and I’ll meet you in the Visitors Centre.

So we did and he took us all over the Tracking Station and in Tidbinbilla they’ve got a very big dish and up on to the platform of the dish and then when you’re moving around the main building, remember this is the 80s. In the corridors, either end they had 29 inch analogue TVs and in the operational areas, the same thing and in their conference room which was huge, two teleconferencing phones on the table and in each corner of the room another TV and they were showing live coverage from Cape Canaveral and he said, “Ah John, one thing about this we don’t travel as much as we used to with the technology.” But I always remember, that the only thing Dad could say was “gee whiz” walking around the station. And the way this bloke changed completely.

“Then about three years ago, I went to Tidbinbilla again, this time with my brother. It was a Sunday morning and, typical Canberra weather, very very cold. My brother had gone outside on to the balcony to take a photo of the dish, and I was taking a photo through the glass and there was a volunteer guide in the room. There’s nobody there then and he said, “Oh you can go outside if you want to.” I said, “No I’m okay in here.” Then, because I’d been there twice previously, I said to him, “Oh, when you walk in on the path on the way in to the building, the foundation stone of Carnarvon used to be there, it’s not there now. Do you know what happened to it?” And he said, “Oh, yeh, remember seeing it. Don’t know what happened to it, but Carnarvon wasn’t much. They only tracked a couple of Gemini spacecraft.” Well, by the time I left he was under no misunderstanding that Carnarvon did a lot more than track a couple of Gemini missions. Well, perhaps to my embarrassment but the language left no uncertain terms I knew what I was talking about. I was so incensed about it, that when I came back to Perth I rang the Visitors Centre Manager and he was shocked and said, “I might have to have a word in his ear.” Worst person in the world to say to, Carnarvon wasn’t much.

“While I was in Carnarvon at the Tracking Station, I was part of the volunteer fire team at the Tracking Station and then I also joined the Volunteer Fire Brigade in town. After Apollo 13, I resigned and became an Aviation Fire Fighter at Perth Airport. On the OTC site there is now the totally brilliant Carnarvon Space and Technology Museum. I was there at one point when Andy Thomas opened the second stage of the Museum. He actually said that in Houston, and Cape Canaveral, Carnarvon had a brilliant name as a “can do”, um impossible, straight away, miracles take a bit longer. He said being here and seeing the memorabilia really reinforced what was really thought about the place.

“One positive out of many for Carnarvon, I met my wife, Ann, there and that was late 1968 and she passed away in 2011.”

Last year on 20th July (American time) 2019 marked the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing in 1969. John attended the reunion in Carnarvon.

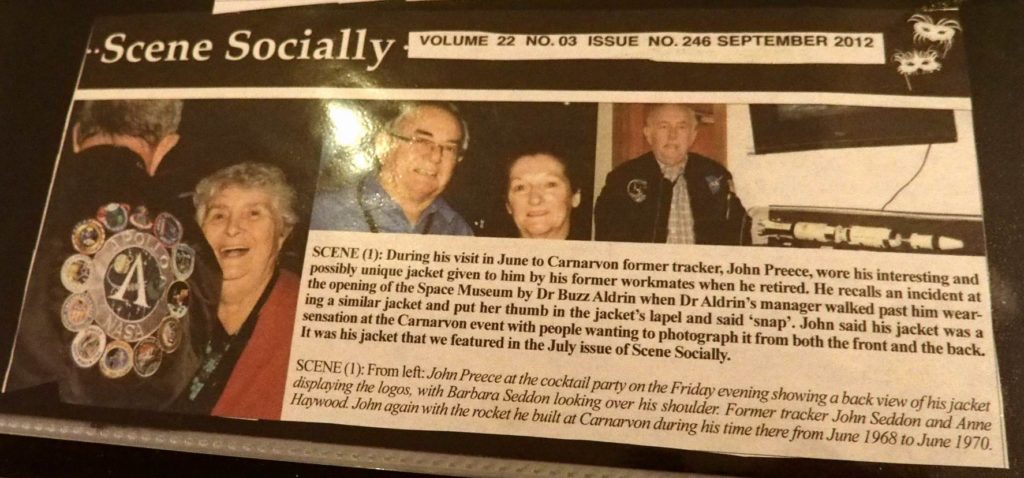

“As far as Carnarvon goes at the Tracking Station, I basically go to the opening of an envelope. I enjoy going to those events and the Museum’s been opened in three stages. The first stage was very minimal but the high profile guest was Buzz Aldrin who was very impressive when I got to meet him.”

“Over a period of time at various events up there, I met Andy Thomas and Gene Cernan. Gene Cernan was a very interesting man. When those VIPs stay in Carnarvon, instead of in a motel, they stay in serviced accommodation. But on the last day, they have breakfast in the premier hotel in town. And I’m sitting there having breakfast and him and his party happen to walk in. And so, we simultaneously were at the buffet and I said – thank you for signing my jacket. That was the night before, organised through a third party. And then they were sitting at the table next to me and of course, people being people, somebody in his party said – oh Gene, you’ve got to try this. This is the Australian delicacy, Vegemite. Well, of course, there’s more Vegemite on the crust than there is crust. He took it in both hands and looked at it and smelt it and “I don’t know how Australians can eat this. The smell alone will kill you.” Finally he put it in his mouth and started to chew it, and of course, the body language was screaming – he wanted to spit it somewhere, and couldn’t. And he swallowed it and said – “I was right, it will kill you.” So I then got up, went over to the buffet, got a Vegemite portion, wrote the acronym for Carnarvon, which was CRO, signed it and dated it and went over to him, handed it to him and said – “Mr Cernan, it’s only right, you signed something for me, I should sign something for you.” He held in both hands, looked at it and a real Texan drawl said – “Well, my son I will take it back to my ranch in Texas but I will not put it in my survival kit. It will kill me.”

“The jacket that I was wearing when we met at Carnarvon and wearing today of course, a little bit of history behind that. After I retired from working at the Airport for 40 years the Airport Operator then known as the Westralian Airports Corporation gave a me a very public send-off, which was appreciated. Unfortunately, for others, doesn’t happen now, lucky to get morning tea. And then the work group I was in was Terminal Operations. They gave me a private dinner. When people knew I was retiring, and seen me, they asked me what I’d miss at the Airport, and I would say, “I will miss the people I’m working with. I won’t miss the politics but I will miss the job and the people I’m working with and the smell of aviation fuel in the morning.” Anyhow, at the private dinner, my former manager said – “Oh we’ve got a couple of joke gifts for you and a serious one later on. And one of them you’ll probably want to keep beside your bedside locker.” And anyhow, then she produces the Airport flag. And then a jar with a clear liquid in it and the jar was stuffed with rag, turned out the liquid was aviation fuel. They’d gone out on to the apron and asked one of the engineers to put aviation fuel in it and he asked – what do you want that for? Oh, John’s retiring, yes. No problem. And I’ve still got that jar of aviation fuel. I think it’s matured, it’s aged and it’s got worse, blow your head off. The serious gift was the jacket which I found out later, it’s a genuine jacket and bought off the NASA website and it wasn’t cheap which makes me appreciate it even more.

“I retired due to ill health in 2010. Yeh, and then I did six years in the State Emergency Service, not climbing on rooves but in an Admin Operational Area as a Duty Officer. As a Duty Officer, Department of Fire & Emergency Services here, they would, if they had job for the unit, they would ring me on fortnightly rotation depending on what the job was, whether it was one team or it was a unit activation because of a big storm or something like that. And I was also trained as an Air Search Observer for the SES and then because my health deteriorated, I had to give it all away.

“Oh, look this has been great Suzanne. I can’t think of anything else to say. I’ve covered it all off.”

(John Preece was interviewed on 27 July 2019)