Mal Lancaster was born in 1941 at Allora on the Darling Downs and grew up there. He became a Press Photographer with the Defence Department and his favourite subject was the F-111 fighter jet. This is his story:

“I attended Warwick High School and then I was in Junior year and my father became very ill and I had to leave and become bread-winner for the family. He was off work for well over 12 months with some rheumatic problem and he couldn’t walk. I worked within a butcher shop in Allora and then that wasn’t bringing in enough money so I moved up to the Warwick Bacon Factory and worked there as, what they call a “boner”, breaking down a beast for exporting. That was bringing in enough money to look after the family.”

When Mal’s father was well enough to work again, Mal decided what to do with his life.

“Allora itself was a very small town of some 400 people. Unless your parents had property, a farm or a business, there wasn’t much there to do so I applied to join the Navy in 1959 and was accepted. I always had a fascination with electronics and when I applied to join the Navy I wanted to work on electronics of aviation. The Navy had their naval air station at Nowra and I went there. They found out that I was colour-blind. Now being an electrician, it’s not very good to be colour-blind because you don’t know your colour coding, your wiring so I didn’t achieve my initial dream but for every door that closes a new one opens and I ended up in photography. Now, the moral of that story is you don’t have to worry about being colour blind to be a photographer. I still can’t see their logic.

“At that stage, there were about 40 recruits all looking for various roles in Fleet Air Arm and when I missed out on, going into the electronics side, I sat for this aptitude test and there was only four out of the forty that had the right aptitude to go into the photography side and fortunately, when I look back over my past, I was one of them. At that stage, of course, the Navy, the photographic side was related to map making and so I thought the government of the day had decided to disband the Fleet Air Arm and with that went the role of map-making. So I was fortunate enough at that stage the Navy had taken on a new role by being open to the general public. They appointed a person, Mr Tony Eggleton, to be Chief of Naval Public Affairs, which I saw as a bit of an opening for a photographer to be working within that area. So I applied to go to Canberra to work in Navy Public Affairs and I was also accepted for that so I was a bit lucky, charmed, I don’t know what but I ended up there working with Tony Eggleton and Mr Phil Hobson who was also a War Correspondent, a War Photographer from Korea. So I had some fairly good initial training into that role of Public Affairs. And that carried me right through till I sort of retired from the Navy in 1969. I remained in Naval Public Affairs tripping around the world on ships.”

Mal was at HMAS Albatross, Nowra where he learnt all about photography and map-making. Until then he had had no interest in photography.

“Nowra was the central base for their Naval Air station, all their aircraft which operated off an aircraft carrier. So that was their central base for that. And map-making? No, I didn’t really have any interest in it prior getting that position in the photographic world. But once I got in there and, the training was a 12-month course which was quite intense, learning about the photographic side, the requirements. Because we were still using aerial cameras for reconnaissance work. It was fairly intense training. Not only was it the still side. We did cine work as well, cinematography because all aircraft landings on and off an aircraft carrier had to be videoed in case of an accident. So we had to learn how to process these 16mm film and have that available should there have been a conflict or crash on board the aircraft carrier. That had to be available to the inquiry almost immediately. So it was pretty intense. We used to work under some pretty basic conditions to do all this but it was a very interesting course and this went on right throughout my career. You always updated courses throughout your career.

“Going back, I think the Navy was one of the first branches of our military to recognise the need to communicate with the general public. It wasn’t that long after World War II that the Navy appointed Tony Eggleton to make the Navy’s work more available through communication to the general public. And then we moved, on, not so much longer, the Vietnam war where, that war became available to everyone in their lounge room. It was a dramatic change, the video side, television side, to the way it was reported. Prior to that, military had control over all communications so they would only release what they thought the general public needed to know. So come television, there was a totally different attitude. The military, although they thought they had control, they probably didn’t with television. CNN probably had more money than most defence forces. They could afford to put people on the ground and television, satellite dishes and whatever to stream that news back immediately. I worked with the Navy in Vietnam and produced the only film of the Navy in Vietnam called “On the Gunline” (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xlw8QgdqfCk ). But when you see how we did it as opposed to the television boys. We were still in the Dark Ages. Even though, we’d shoot our film. We’d then send it back to Canberra. It’d be picked up, then it’d be processed and then, four or five days, six days old with the news. Whereas your CNN stations and so forth would stream it back almost immediately. It was a major change for the world, television allowing people to see exactly what did take place almost immediately.”

Mal was posted to Navy headquarters in 1961 under the supervision of Tony Eggleton.

“The Navy had just established that position in Navy Public Affairs and Tony Eggleton was one of the first. He was a brilliant man. He went on to become Press Secretary to five Prime Ministers so there’s a degree of brilliance there. He was a very, he was a stickler for finishing your day’s work. He thought there were three types of people – those who came to work and went home, those who came to work and probably gave a little bit more to the job, but the people he wanted to work with were those that came to work and were prepared from the moment they got to work that morning to complete their day and not go home until the day’s work was completed. So you were prepared for any issue on the following day. So that was Tony Eggleton. He was a hard taskmaster but a good one. The things he taught me I actually used in a lot of my planning to do major jobs.”

“At that stage I was nearing the end of my term in the Navy, in the late 1960s, and I’d just got back from doing a tour of New Zealand to publicise the H.M.A.S. ANZAC. On the way back I was told that as soon as I returned I had to board a ship and go straight across to Tonga to record the Australian Navy’s input in to the coronation of the King of Tonga. It was very interesting because I think it was a New Zealand film information centre which had the rights to film the coronation and distribute the information around the world. When I got there I ended up talking to this pilot of a commercial airline. I asked him when he was departing after the coronation. He said – yes, I’m leaving at 2.30 in the morning. The King had put a ban on all aircraft in and out of Tonga for 48 hours. So how this came about I don’t really know but he got special dispensation to fly out at 2.40 in the morning. So I organised with him to take all my film, video, the TV footage and the stills and drop them off in Sydney. There’d be someone there to pick it up. This did eventuate. We got a world scoop, first in the world and got some bad friendship out of the Kiwis for that. It was fascinating, the coronation itself. Such a poor country but it was like a Disneyland coronation. Everyone dressed differently, all the food laid out on the Tapa Matting. They slaughtered something like 400 pigs for the coronation, so many chickens. But it took years for the country to pick up after that, after that coronation.

“My initial training was on; I can’t even think of the name of it. It was a wooden camera, for my initial training and it was an 8 x 6 format, 8 inches by 6 inches, what’s that 20 x 30 cm format camera where we learnt how to, how to manipulate, how to process large format photos, and learnt about lighting. We learnt about lenses using that camera. From that we moved on to one of the latest cameras which was a 45 Linhof which was a beautiful camera but for press work it was very difficult because you had only six slides, graphic back I think they used to call it which would take six sheets of film so your job was confined to six sheets or if you had graph matic, you’d have 12 sheets. So you always had to get your shots. That’s why I got known as “One Shot Mal”. But from there in the probably mid-60s, with the advent of the Nikon camera, the 35 mm and then it just progressed from there. The Nikon got better and better and better, more lenses, better lenses and the whole thing was confined then to the 35 mm world until now of course it’s all same thing but digital. What I have at home is very similar to what I started with, what’s called a Thornton Pickard which was developed in turn of the century 1890 or something and it’s very similar to my Rosewood camera. But it was beautiful you could do everything on that camera that you can’t do today on a modern camera. You could correct parallax, you could have a rise and fall in front, you could, if I could use this word, Scheimpflug. You could actually do a Scheimpflug rule which means that you could put the plane of your camera and took the lens of your camera to each other so you increase the sharpness around the circle. Yeh, so it was a beautiful camera, really was. But you can’t do that today, not with the modern digitals.

“That was probably one of the beauties of my early training that you were a craftsman in that area. We were trained by a craftsman, a British photographer and he was an artisan. That’s how he came out here as an artisan and he trained us in all the work, knowledge. He passed on all the knowledge of photography which, which was fantastic really when you look back, Knocker White. I never ever knew his Christian name except Knocker. Knocker White is what I knew him as and he was the chief and we were little naval airmen. His knowledge of photography was just unbelievable. So it’s carried me right through life. You can still use some of the things he taught us and that with modern day cameras, simply by getting a bit of height and tilting your 35mm you’ll increase your sharpness or whatever. But it’s only with that background knowledge that you can do this sort of thing. He would have trained hundreds and hundreds. We meet as a photographic, what would you call it, group of people. We tend to meet every two or three years somewhere in Australia as an association. It’s not even an association, we just meet. We go to the meet, we all turn up so, normally you get about 60 of the old people still turn up, have a drink, talk about what they have and haven’t done.

“I think I owe a lot to my naval service. Initially, even though I came from a very small town, my direction in life was probably pretty minimal and my going in to the Navy sort of broadened my whole outlook having travelled the world with them, mixed with various people from the most junior to the most senior person. It really I think built my character. I’d hate to think back if I’d stayed in Allora just exactly what I’d be doing now. So it allowed me to travel the world and that’s probably one of the greatest educators of all, meeting people from other countries and working with those people. And one of the good things with the military service was that you had the opportunity to work with smart people. You’re out there to do a job and they expect you to do it. But I still carry a lot of my early training. I’m a bit anal about things I do you know, I still have to polish my shoes and things like that.

“You just spoke about character. This is one of the areas that teaches people to be able to live with people. On some of the early warships, 30 odd people would live in an area of probably 20 x 30 feet. Now that was a living, you lived there, you ate there. You’d have to put your hammocks up of a night time. You had a little space, a locker, to put all your gear in. You couldn’t leave gear lying around. So it built a character up. If someone sort of didn’t want to comply, he was very quickly put in his place by 29 other people who lived there. So it did build a character.

“I think being punctual is a trait that we’re all losing. The world is losing now. I think if you say you’re going to be somewhere. If you’re doing business with someone, I think that’s a compliment to be able to be there on time, a respect and everything else. If you don’t, the person’s going to look and say – well, does he really care about, you know, this appointment or does he not? I think that’s very very important, punctuality.

“I look around now and I think it’s unfortunate, it’s all about “Me”, rather than having a real care about your friend and I think this is one of the good things that the military has taught me, always look after your mates and that is not just your mates, that’s everyone. I’m in Kiwanis, which is a service club and our major role is raising money to look after children and whenever I’m with children, I’m always referring back, now make sure you look after your mates. When I was President of the RSL, I’d finish up my meeting simply by saying – what have you done for your mate this week? It was just a reassurance. Don’t forget your friends.

“Young people probably do it now but in a different way. They pick up a telephone and think they’ve communicated with their mate, their friend. I don’t think that. I think everyone needs companionship. Everyone needs to be touched. Everyone needs to be eye-balled. You know what I mean for want of a better word and I think we tend to miss that. You jump on a bus now and everyone’s got their head down looking at the ground, there’s a telephone in front of them. I think that we have to move past that and get back to just some good verbal communication.”

Mal returned to Sydney from the Vietnam War in December 1968.

“I was sent to Vietnam only a couple of months before I was due to retire from the Navy. And this is where I shot that film “On the Gunline”. That was working with the helicopter boys and the 135th, called it Emu Squadron, Engineering Maintenance Unit they call it where the Navy pilots were working with the Americans. I was on board “Perth”, “On The Gunline”, which was a Para 38, 39 parallel, whichever one it was. And then back down to Saigon to Headquarters. I was also with the Navy, filmed the Navy divers up there as well. That was all incorporated in to the film so it’s basically the Navy’s involvement in Vietnam. It still pops up every so often on ANZAC Day.

“From there I wanted to finish my time. I got out, I think it was 6th February 1969. I wanted to stay in Sydney for my retirement and they wouldn’t let me because they were short of people so I went round to Adelaide on the “Sydney” and that was where I finished my time in the Navy. That’s where I met Bev, my wife. Then the romance started. When I retired from the Navy I got a job with Air Force Public Affairs for the arrival of the F-111. The arrival had been delayed so I spent a year in Canberra and our courtship was a letter every night and a phone call every second night between Adelaide and Canberra.

“I met Bev at a car rally. A friend of mine who was there, Peter, had retired from Navy. He came down and met me. And he said – Mal, I’m going out on a buffalo lodge car rally, would you believe! So we went to the car rally and it finished up at someone’s house down at Port Noarlunga and that’s where I met Bev. She was a nurse and she was down there with her Aunty whose place we stopped at. And I met her and that’s where it all started. We were married in Glenelg in Adelaide. It wasn’t a big wedding, probably, 40 or 50 people there. Bev’s parents lived in Glenelg and my parents were still in Brisbane. Mum came down for the wedding. The day after the wedding, we had a honeymoon on Hayman Island. So the next day we took off for Queensland to catch a flight from Brisbane to Hayman Island and made that. I wouldn’t do it today. I think we drove up in about 23 hours or something, terrible. So yeh it was good. I had some friends from the Navy. I think best men were all navy men. Looking back, we’re getting close to our 50th anniversary.

“I applied for a position with Air Force Public Affairs to set up the office of Air Force PR in Queensland because the Air Force had no PR representation in Queensland. They used to fly people out of Canberra to go up and do jobs, which was less than successful. So with the arrival of the F-111, they set up this position which myself and Gerry Thurlow set up the office in Queensland. The aircraft arrived in June 1973. I flew out on a Phantom Jet to meet them off the coast of Brisbane, north coast of Brisbane out on Moreton Bay. We photographed the first six as they circled. That was video and stills. Those images once again went round the world and I stayed with them until I retired in 2000 and doing that work.

“The

35 squadron which flew Caribou aircraft were having a morale issue. The aircraft was going to be sort of

retired. The guys really never had a

plan of what was going to happen so the morale of all the troops was down and

the CO of the squadron came to me, said – Mal, can you do something for us,

publicity-wise. So I sat down with him

and planned this photograph. The role of

the Caribou was to do what they call stol drops. So it wouldn’t land but it could and load to

the troops without landing and pinpoint drop it. So I said if we could set up a photograph of

the Caribou coming in, doing a stol drop so I’ve got the big parachute plumed

out the back of the aircraft but it’s still off the ground and what they call a

lapse coming out the back of the aircraft.

He said – you’re asking a lot. I

said – Oh we can do it. So with using

what I’d been taught initially, planning, from the Navy and then from Tony,

make sure everyone’s in the loop and knows what’s going on. We sat down there and we worked out

mathematically what lens to use, where he had to pull the pin to drop the

parachute or pull the parachute up, the load up, and I would be directly in

front of him with this long lens. So

capturing the lot. It worked. And from that we had stories in the paper

because no one had ever seen this before.

And from that image, we also had a great big poster for the troops to

send and put up. It lifted the morale of

the troops. They could say – look what

we can do. So I put a lot of that down

to my initial training with Tony Eggleton.

Communicate – you must communicate properly and then the initial

training I did with the Navy photographic section on learning all about

lenses.

“There

was that one and then there was another one.

I had a call from Jake Newham who was Chief of the Air Force at that

stage. He also flew the first F-111 out

to Australia. He called me one morning

and said – Mal, we have a, a problem. One

of the lobbyists in Canberra is saying the aircraft, the F-111 can’t carry out

the role that the Department is saying that it should be doing. So I said – Sir, well, what do you expect me

to do. I’m a mere photographer. He said – I want one of your photographs

that’s going to tell the story. So with

that, I always had in mind that I’d like to be able to show all the munitions

that the F-111 was capable of carrying.

And with that, he said – make it happen.

So I then got a call from the Commander of Amberley asking what the hell

I was doing. And I said – well this is

the way it goes. It took two, nearly

three months to get all the munitions out to Amberley. I had the aircraft for four days, then it was

cut to two days. So trying to put 30

tonnes of bombs in a position that was going to be done in a day and a half,

the sun in the right position, and everything else. It took a lot of planning. But, it worked. It did work.

The image and the story that went with it went around the world and it

did save it. The lobbyist was saying

that the aircraft could only operate out to 500 miles, which was a total

lie. It could operate out to beyond

1,000 nautical miles. And that was the

end of that story. You know, the

photograph really saved it, helped save the day.

“I

don’t think anyone except the people who flew that aircraft and controlled it really

knew how good it was. It was a brilliant

machine. It could drop a bomb basically

on a match-head. It was stealth. It could do work at sea, sea operations. It was fast.

It could deliver a bomb, pop-up bomb and get the hell out of there. So it couldn’t be attacked. It was a brilliant aircraft. From my point of view, photographically,

working with those people who flew that aircraft. They were as proud of that as I was as eager

to photograph. Talking to them about a

concept to get an image was easy as long as it promotes the aircraft. So I really had a stage that I could work

from and all the actors wanted to be part of it and it was brilliant. As long as my concept was going to get a

result, they’d help me out anyway. At

one stage, I wanted to get about 19 aircraft and I wanted to get them all in a

line. Even the Commander said – Mal, I’m

not going to approve that. You’ll have

to go down and talk to the Warrant Officer down on the flight line because

they’re his aircraft. So I went down and

spoke to him. He said – my God you give

me a headache. When do you want them? It was that sort of attitude that allowed us

to get the good publicity and the photographic work. It was tremendous.

“But

every time I looked at that aircraft I saw a different image, depended how you

looked at it, and how you photographed using long lenses, it changed the whole

visual impact of that aeroplane. You

could get underneath it with a wide angle lens and once again it was a totally

different view of that aircraft. I was fortunate

enough to photograph it whilst we were tanking and took fuel from an airborne

tanker. I was in the cockpit, getting

that angle. I set up another photographer

from the ABC in the actual aircraft, the tanking aircraft. So we had a two-way coverage when they’re

tanking. That had 2.2 minutes, I think

on ABC News. Never before has an article

run so long. It was unbelievable.

“Working

with the ground staff, they were as enchanted with that aircraft as the pilots

were, the air crews. So they wanted to

see the best I could do for them. I’d go

away on exercises all around the world with the aircraft. And, they’d be doing work. When they’re on an operation, that’s all they

see. They work hard, long hours and to

interrupt their trains of thought, sometimes, you’ve got to pick your

time. So it was always over a beer the

night before – what’s a good time to come down and, photograph the troops so we

get it in the newspaper, show them what you’re doing. Oh, okay, we’ll make a gap for you. And they’d put a gap in their day just to do

that work. So you know, it was easy

working with those people. As I said,

every time I saw that aircraft through a camera lens it was a different beast.

“An

image is only open to your imagination.

You can do anything you like.

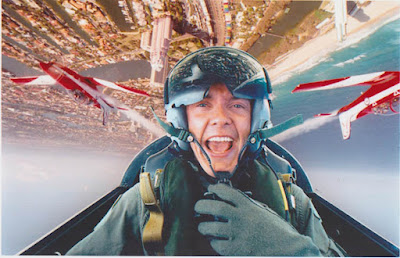

Now, I’ve got an image here, a selfie, probably one of the original

selfies of me in a Mirage jet with two F-111s behind me. I go back to my initial discussion about

working with Tony Eggleton and “prepare for your day”. I knew the day before I took this image that

I was going flying. So you sit there and

you work out – what can I do, what can I do that’s different. You don’t have too much room to work in. So this particular image, I’m looking at the

original “selfie”.

“I

was using a fish-eye lens but before I even got into the aircraft, I’d sat down

with the three pilots, two of the F-111s and Mirage pilot and I explained

exactly how I envisaged this photograph, so that when we got up there, they

were aux fait with what I was doing. And

when I’d call the aircraft behind me, the F-111s up higher, higher, higher and

split. They knew exactly what I was

trying to achieve. And that’s where it

was so good working with these people. Everyone

knew, you’re all in the same loop.

“This

image reminds me of another image of down the Gold Coast where the car races, the

Formula 1 race they have down there. The

organisers of the race wanted a high Defence input and at that stage we had a

lot of commitments overseas. And it came

back, someone said – are we going to get a visible return on our input. By that they were talking about having lots

of press, television coverage. So

straight away I started working on another similar shot to this but not with me

in the cockpit, with one of the F1 drivers in the cockpit a Mexican driver, Adrian

Fernandez. I spoke to the Fernandez’s

team leader to explain what I wanted to do.

And they said – you’d be lucky, he’s crazy, he’ll forget to take the

picture. I said – no I could arrange

that. So I had the pilot set up so the

pilot took the image. All he had to do

was tell the Mexican to smile. I wanted

the Roulettes, which is the Air Force aerobatic team upside down, over the

finishing line at the F1 races on the Gold Coast with the Mexican pilot with a

big smile on his face. So, it all

worked. The picture went around the

world that night. And I said to Fernandez

– what’d you say. He said – here Mummy

here’s a nice shot of me. It was a great

picture, a great result for the Air Force on the day and a great result for the

F1 race on the Gold Coast.

“When

I left the Navy, the position I took up with Air Force Public Affairs was an

actual Public Service position. For a

period of probably 20-odd years the Navy and the Air Force were all civil

positions because they drew their strength from the media. The Army was the only one that maintained

people in uniform because of their situation being overseas. So when I was appointed to the position, it

also required that I take on the commission in the Reserve which would allow me

to go away with the F-111s on exercise or the Canberras or the Chinooks or

whatever. But it made it easy for the

system to call me up overnight and I could be in uniform and jump in the aeroplane

the next day without having to go through the civil procedures of going

away. So it was just a signal would come

out – I’m called up for x amount of weeks and that was it. It worked well actually because when you’re

carrying a camera around on a foreign military base, the first thing you do is

get arrested. So if you’re in uniform,

you’re part of the group. The Commander

knows that they have a PR person who’s going to be doing this work. That gets read out so you have a degree of

flexibility.

“There

are some times when you get an added bonus for the work you do. I was flying.

I’d just done some aerial photography in an F4 Phantom back from

northern NSW. The pilot was Dave

Rogers. He was the Squadron Leader at

the time, who then went on to become Chief of the Air Force and it was Dave who

let me fly his F4 in a twinkle flight from northern NSW back to Amberley. The Phantom was an interim aircraft prior to

the arrival of the F-111 aircraft. We

were down off Evans Head in NSW doing this photographic work because that’s our

airspace. We could basically do what we

wanted to up to a certain point. And on

the way back, the pilot said – here mate it’s yours. So I flew the Phantom from Evans Head up to

Amberley in a “twinkle manoeuvre” which is when you put the stick

hard over and you just rotate through the air.

It was great fun.

“Although

I’ve spoken about my role with the F-111, there were several squadrons out of

Amberley. The Chinooks, Iroquois and the

Canberras. I worked with all those squadrons

and I thoroughly enjoyed my time with the Chinooks and the Iroquois because you

got to be part of the crew, landing, seeing what they did, the work they did,

helping them with the work they did. And

one of the big, big jobs that the Chinooks did, I think it was in the early

80s, the “Waigani Express” ran aground in New Guinea. It was a container ship and the only way they

could get that ship off the beach was to take all the containers off the

ship. There was something like 230

containers. And the Chinooks actually

went up there and lifted these containers off the ship so it could be

refloated. And that was an unbelievable

exercise.

“Not

so long after that a similar thing happened off Caloundra. Another ship did the same thing and Chinooks went

in and carried the containers off which allowed them to refloat that ship as

well. I used to go out with the Iroquois

mainly when they were doing flood relief work.

The same with the Chinooks. So if

we didn’t go out and cover that, the press probably wouldn’t take that

side. They’d do the other side whereas

my being on the ground with the Chinooks, I could get both sides and so we

always had a foot in the door and the media with the images of the guys working

with the aircraft doing its role.

“One

of the other enjoyable sort of assignments I had was working with the Chinooks

in lifting eight A20 Boston aircraft from World War II out of New Guinea. Right up along the north-west coast of New

Guinea and these aircraft crashed because of what they call “the Black

Friday”. They actually ran out of

fuel. We pulled eight of these wrecks

out of the jungle with the view of having them restored, one for Australia and

one for Papua New Guinea. I’m not too

sure where they’re at with the one for Papua New Guinea but the one in

Australia, has been taken and restored, not to flying standard, but certainly

to have it in an identical reflection of what the aircraft looked like back in

1940.

“Very

early in my time with Air Force Public Affairs, would have been probably in

1970, 1969 probably, the Air Force had received information that a wreck was

sighted in the mountains of Irian Jaya.

It turned out that this was an Australian DC3 returning from Borneo with

28 Australian POWs on board. I think two

of which were nurses. The aircraft had

remained there up until 1969 from when it crashed in 1945 I think. The Number 9 Squadron from RAAF Amberley

operated helicopters so we flew up in to an area called Lake Enarotali and set

up a base camp. That was at 9,000 feet

and I think we were operating up to 13,000 feet and it was an actual glacier

line. The glacier was just above

us. The Iroquois was operating on its

maximum performance. They had to strip

it right down, use minimum fuel and they could only take up a pilot and one

person who was lowered down to the wreck to retrieve the remains of these

people. They went up there a second

time. I wasn’t on that trip but I think

they brought back more remains from that on the second trip. The aircraft was actually found by a Seventh

Day Adventist pilot who was working up in that area. He’d sighted it some five or six years prior

to that but when he went back he couldn’t find it. The mountains are so precipitous, it’s easy

just to fly over and not actually see anything there. He saw it again about five years later and I

think he took a Satnav position which made it a lot easier to find it. He reported it back to the Australian

Government that he had an exact identification of the location of this wreck. Then the Air Force went up there and

extracted the remains of these people who’d been there for some 27 years. That was a very interesting operation, very

interesting working with the locals, Indonesian.

“I

really don’t know if they identified them.

They certainly could identify some of the bones had been female. Earlier this year I had call from a young

lady who’s doing research on this crash because her uncle was one of those

people on board. And she’s writing a

book on this now.”

Mal

won the NIKON Press Photographer of the Year award following a dramatic rescue.

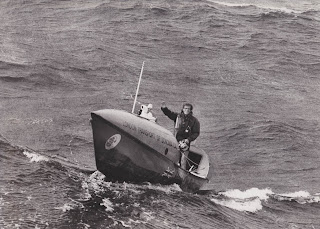

“That

was very interesting. A young Englishman

who was in America set out to row a boat by himself from San Francisco to

Australia. He almost made it. It was about 11 months he was rowing this

boat by himself and the call came out he needed help. There was a cyclone coming on, off the coast

near Cairns and he needed help. I flew

out with the Orions three weeks before we actually rescued him to identify his

position. He did ask for something

specific which they dropped in a box down to him. I can’t remember exactly what it was but

three weeks later we got the call that he needed help to be extracted because

the cyclone was so bad off Cairns that he looked like going under. I went out with the Navy and the world press

were there at this stage. That’s how

much interest was in it in Cairns. The

world press was on board the navy boat.

We went out. We couldn’t find

him. The boat came back and I stayed

with the boat. The world press got let

off on to Lizard Island I think. And I

came back to Cairns with the boat and I went up and had a shower, had something

to eat and then the skipper rang me and says – Hey, I’m going back out

again. We’ve got an exact location of

him, he needs help now. We went out and

found Peter Bird who was the gentleman.

And I shot video and stills of this which, when we arrived back in

Cairns the world press swamped me and we had all our stuff went around the

world. I was even offered $10,000.00 for

one image. But working for the

Government at the time I couldn’t sell it.

I flew straight back to Brisbane and we distributed the stuff throughout

the world. It was very interesting times

and then towards the end of that year I submitted my imagery of that to the

Nikon Press Photographer of the Year Award and I was successful in getting the

Nikon Press Photographer of the Year Award for the imagery of that assignment.”

Mal

received further awards for his work.

“I was recognised for my work with the Chief of the Air Force Commendation, on a major parade which I was out there covering for the press anyway. When they called my name out, I was quite sort of taken aback with this to get the commendation. It was such a surprise because doing a job that I absolutely had a passion for and loved, it wasn’t a job, it was excitement every day because every day was a new day.

“The RAAF over the years have maintained a collection of work that records the history of the Air Force – authors writing a book about a certain subject, art, painting, you know, whatever. Then they had the photographic one in there and I was somewhat fortunate to pick up three or four of these Heritage Awards which means that your work is locked away for posterity, for someone else to view down the track somewhere.

“I was on the New Year’s Honours List in 1994. I was told about this award by the Honours Awards in October, if I would accept the award. Naturally you would. So I had to keep it all secret, not tell anyone. And then I was on a plane back from America with my wife. We’d been over there for a conference and I was on the plane. As we’re sort of half way through, we’d just turned into the day on New Year’s Day. I said to Bev – guess what, I’ve just received an Honours Award. So she spoke to the hostess and the hostess came back with a bottle of champagne. So that’s how we celebrated that award at 35,000 feet, somewhere over the Pacific. It was what they call a Public Service Medal, which was for my contribution to working as a civilian within the military system. It was unique, that I was part of their system as a civilian, even though I had a commission in the Reserve. I was part of their system and someone there recognised the fact that the work that I was doing was helping them out. So it was good.

“The Reserve Force Decoration, yeh. I’d spent more than 15 years on the Air Force Reserve and there is some criteria you have to be called up a certain number of times during each year consecutively over that 15-year period in which I had and it’s an Air Force decoration, called the Reserve Force Decoration which, I don’t know what year I got that but it, I suppose it must have been ’69, ’79, mid 80s or something like that.”

Mal completed a book of his pictorial work of the F-111 called The Flight of the Pig.

“The Flight of the Pig. I don’t know how many images I had of the

F-111 but I thought it was only right that I share those with people in the

form of a book and it was the 25th, I think, anniversary of the F-111 that I

sort of compiled all these images in a book called The Flight of the Pig.

People still ask the question, why was it called “The

Pig”. It was basically named

initially, because of its droopy nose.

It has a somewhat droopy nose and it was named after an ant-eater from

South America, the Aardvark. And that’s

how it got the name The Pig. But it was

interesting the images, if I was to do it again, I’d do it totally

differently. We probably all say

that. But, the interest that it created

around the world was quite good because I had calls from just about every major

country in the world, Russia, America wanting a copy of the book. It’s something, a legacy to leave.

“I

retired in 2000. I’d reached a point at

59 where I thought that I’d chased enough fire engines. Just before I retired, I was given the role

of introducing digital photography to the military. That gave me another lease of life. I hung on there for a while and our office in

Brisbane was one of the first to send a digital image to the “Courier-Mail”

when the “Courier-Mail” started receiving digital photography. I also had some reservations about what was

happening up in northern Australia with “children overboard” and I

put pen to paper and forwarded my suggestions, my thoughts to certain people

and the reply was – have I thought about retiring. I look back and I’m glad it all happened that

way. The time was right. And I can’t say anything bad because they did

offer me a redundancy and everything else.

But if I hadn’t written that letter outlining my thoughts on what was

happening, I probably would have stayed there till I died. So now I’ve had 16 good years with my family,

recent grandchildren and I’m healthy, probably wiser. I was going to say wealthy, but healthy,

wealthy and wise, healthy and wiser.

“Bev

had played mother and father to my children.

I was always overseas somewhere doing something with work. When I finished I said I’d like to give

something back to the community. At that

stage, in 2000 there was a meeting about setting up an RSL in the Centenary

Suburbs. I went along to the inaugural

meeting and immediately became involved on the committee. Before you knew it I was Secretary, then

President. That was a bit of a learning

curve. Because having worked with young

people all my life, with an idea, let’s do it, it gets done. Then I started working with old people and

there wasn’t that passion or urgency to get things done with the people I was

dealing with. So I sort of had a

problem, worked out that it was just me that I expected everyone to work on my

timeline and channel and everything I’d say.

I had to sort of pull back and start realising that not everyone thought

the way I did or reacted the way I did.

So that was a good learning curve for me.

“When

I was with the RSL, we basically started out with nothing. We had no representation in the Centenary

area. There were a couple of people in

the Chamber of Commerce who thought we needed a war memorial. So they started planning to set up a war

memorial on the corner of Dandenong Road and Arrabri Avenue. That got momentum. We got the basics set up, handed over to

us. From there, our numbers started to

grow in our local sub-branch and we put in for grants and we started putting

more sort of memorabilia into the memorial, new flag poles and remembrance

plaques. And I’d like to think today

that by us doing that, we have brought our community together. Certainly on ANZAC Day because we have up to

4,000 people now come to our service and from the initial service was 200 to

300 people, I think we have made people more aware of our history, military

history.

“Then

I became involved with Kiwanis, which is an International Service Club and that

basically is about raising money for children.

I’ve enjoyed my time with them because I think the more compassion you

can show throughout the world. I’d like

to think we make it a better place. I

think if you’re going to put your hand up to do something you should become

totally involved. So I ended up

President for three years or something. In

that period of time, a world-wide project was introduced into Kiwanis. In 2000 UNICEF started out a project called The

Eliminate Project where they were going to vaccinate 60 million women and

children throughout 60 countries against maternal and neo-natal tetanus, a

deadly disease. In 2010 just 10 years

after they started the project, they ran out of money. They then came to Kiwanis International to see

if we could help them out by raising $110M in five years. So Kiwanis International accepted that

project. They went out to all their

clubs around the world, something like 13,000 Kiwanis clubs around the world,

640,000 members to raise the $110M in five years. It was great seeing at the end of the five

years that we’d raised $110M. We’ve

raised $57M in cash, so they had that in the bank and the rest was all pledged

so that will come in, progressively over the next couple of years but it

allowed UNICEF to go ahead with that project and continue the vaccination. Of about 30 of the 60 countries, there is

only about 13 now that they haven’t been completed. It was a world life-changing project. And it’s nice to be part of something like

that.

“The

tetanus spore comes out of the ground.

So the problem is just basically dirty birthing practices. In actual fact the project has done more than

that. It has resolved the problem of

neo-natal tetanus and it has empowered a lot of women in these Third World

countries, dominated by the men that women be told what to do. All of a sudden they’re making the decision

themselves. They have to go up and see

the nurse to get an injection. So it has

empowered a lot of women and there’s been a major turn-around throughout some

of these countries, empowering these women to be part of the community. So the outcomes were two-fold which was

good.

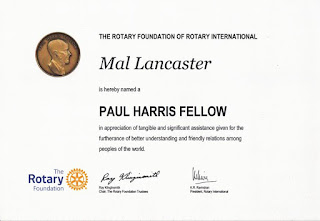

“I

was down in Melbourne with my grandchildren and I got a call from the President

of the Jindalee Rotary Club asking me if I’d come along and be one of their

guest speakers. I said – yeh, yeh. He said – when could you do it? I said – I’ll be back in Brisbane on whatever

the date was, make that Tuesday night so, did that. I went and gave a talk about The Eliminate

Project because being a sister service club they’re always interested in the

work that other clubs do. And, so I

spoke about how we went about it, how we raised funds and the problems with the

tetanus, and exactly how it affected them.

And then I said – any questions?

They had questions and I answered those and said thank you very much for

your invitation, went to sit down, they said – don’t sit down, we’ve got

something here for you. So then they

started reading out this long narrative about the Paul Harris Fellow then they

presented me with the Paul Harris Fellow medal for my humanitarian work. And it was a bigger thrill to know that a

sister club recognised what I did rather than my own club. You know, I was gobsmacked to receive that

and it was quite unique, the fact that I am not even a Rotarian. So, you know, that doesn’t happen too often

apparently. But it was all the work that

Kiwanis did really and I was only leading the club at the time and I suppose

that’s how it came about but the recognition is there for the work that Kiwanis

did.

“

There’s

one other thing that I’d really like to discuss is the Centenary Historical

Society. Caroline Hamilton asked me if I

could help her out a couple of years ago to recognise the efforts of one of the

early, I think he might’ve been the first pilot in Queensland, Thomas Macleod. What she really needed was someone to run the

project, raise the money to be able to put a plaque or a plinth up at the site

where he completed his flight, to honour 100 years since the first flight. So I took that one on and we raised the

money, we put the plinth up and it was a successful day. But, it was just great working with the group

on a project like that. Thomas Macleod

was certainly a man before his time. He

was a pilot, had so much forethought. A

lawyer at 21, owned a boat, started flying, did all his training in the back

yard at Hill End I think it was. And

then set up this contraption which he flew for 300 metres, down a slope, first

flight, set up his own simulator in his back yard, went on later to become one

of the directors of QANTAS. He took the

pilots that he trained, eight of them from Queensland to the First World War

and flew in the RFC, the flying corps.

He was just a tremendous man. I

had a lot of satisfaction out of doing that one. It was good.

“The

Men’s Shed. That’s relatively new. I’m not doing too much there except helping

out where I can do a few barbecues. I

got them a trailer the other day, wheelbarrow, got them three new members. I can see a real future for that in the

Centenary Suburbs, getting men together, to work together, and talk about their

problems if they have any problems but to have some place to go. Because I think everyone needs “a

shed”. David Cope is among them, an

incredible man. He’s running the

show. But we’re almost at a stage now

where we can start operating this complex down in Monier Road. We’ve got two sheds and a place to work in,

demountables. It’s looking good

actually. It’s fantastic. We got a shed, I think they call it a

Kingstran shed from the military. They

didn’t have any use for it, brand new.

They donated it to us and that’s all erected with the help of local

people. I think we’ve got every grant

known to man to help us do this but it’s all done. I’d say by the New Year, start of 2017 that

it’ll be up, totally up and running. And

if I can help them any way shape or form, I will.

“I

hope my grandchildren become damn good citizens. If I have one thing in life is that I’d like

to be able to sort of shed some of my knowledge on to them so they do become

good citizens. They respect people, and

they look after their mates. If I can

impart that, and I’ve already started with them. Not a great deal of success at the

moment. They’re only very young. But I’ll keep at it and maybe, just maybe

that will click in at some stage, yeh.

“We

were shooting a film called “About a Dollar’s Worth” for cinema

release and “About a Dollar’s Worth” was at that stage we worked out

that it cost the taxpayer of Australia one dollar to have an Air Force. It cost them one dollar to have an Air Force,

maybe it was a dollar a week. I can’t

remember. But that’s how it got its

name, “About a Dollar’s Worth”.

And we basically showed them, in that we showed what the Air Force did

for that dollar. And this image here was

shot at Amberley on an Ariflex camera there.

And I’m on the, almost on the piano keys at Amberley Air Force Base with

an F-111 coming in to land over the top of me and I’ve got the reverse position

so that he’ll just drop down in to frame and land. It’s on a very long lens. So that went to the cinemas around the

country.

“That’s

air to air refuelling so you have it, a tanker full of fuel and when an

aircraft requires refuelling, in the air that is, they fly up behind the

tanker. There’s a guy sitting behind

this mirror that you can see and he actually flies at boom down in to an

intake. So the guy then, he stays

connected and the pilot flies and this thing goes in and out as he moves around

and he takes on fuel.

“It was the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Story Bridge and as always, with River Fire whilst the F-111s were operating, they were the main entertainment for the night when they do their traditional “dump and burn”. They do their dump and burn, and so they’d fly in, start dumping fuel and then hit the after-burner and all that fuel exploded into flame. We had an exchange pilot, chap by the name of Anderson from England, an English exchange pilot and I think he was supposed to fly over at 800 feet was somehow the heights got mixed up and he flew over, they ascertained at 169 feet and he flew out and did the dump and burn. I think Andy’s time in Australia was sort of limited after that, went back to England and he went on to become, I think a Three Star General in the Air Force. He just got knighted. He ended up being in charge of the RAF Safety, Flight Safety, just recently got knighted for his work. He told a funny story when the F-111s were, sort of phased out, they had a big send-off at Amberley and Andy was there. He said – Mal I don’t want to see you. Every time I go somewhere I see that photograph. He said – as Chief of the Air Forces Flying Safety, it’s not a good thing. So, it was quite funny but it was good. It was quite exciting. There was a fire station at the eastern end of the Story Bridge and they had a big fire ladder there. And I got up the top of that, once again working with the air crew, to get in the right position. I set a time-exposure on the Hasselblad camera when they came through so it was about an eight second time exposure. And so I had this great big stream of flame coming through the photograph which shows the Story Bridge, the city and everything else illuminated. The photograph probably goes on a wall. The Chief of the Air Force called me and said – Mal under no circumstances is that to be released. Somehow the negative got out and it ended up in the Officers’ Mess at Point Cook. And once that happens, it goes everywhere. I know it was in Hawaii at the General in Charge of Pacific Fleet, I think, in his office. So it went around the world. But it was, a unique photograph, there’s no doubt about that.”

Mal Lancaster was interviewed in October 2016.